How I Became an Opponent of the Death Penalty

Recently, Tunisia’s legal scene has witnessed a broad debate about capital punishment in connection to the heinous crime committed in Goubellat, Béja Governorate. A mother and grandmother died of wounds inflicted upon them and, according to the media, a girl was raped and is still in shock. Many people from various intellectual and political persuasions and social circles participated in the debate. What caught my attention was the great ferocity that characterized the debate, including the contributions from some intellectuals. They should have helped rationalize and deepen the discussion, but here they were allowing their instincts to express themselves in primitive ways.

The issue is not the barbarity of the crime, as that is undebatable. Nor is it the need to punish its perpetrators, as punishment is necessary and should suit the atrocity of the crime. Rather, the issue is the nature of this punishment: must it be the death sentence? Is capital punishment justified in such murder cases? The astonishing thing is that many of those involved in the debate, including “intellectuals”, not only appointed themselves judges to investigate, convict, and issue final sentences, they also got “creative” with how the execution should be carried out. One university professor, presented as an intellectual, was so cynical that she went as far as calling for the criminals to be tortured to death because she saw hanging as a too lenient – nay, comfortable – sentence.

All these unfettered instincts – and how plentiful they are in our current tense situation that brings out whatever filth, rottenness, and barbarity lies deep inside us – only show that we, as a society, have not sufficiently civilized and matured. This is why we are not yet accustomed to debating our controversial social issues in a calm, deep manner and instead deliver irrational and convulsive reactions that sometimes push us toward the abyss. Hence, I decided to delve into the capital punishment issue and explain the circumstances that turned me from an advocate to an opponent, for doing so might prompt others not necessarily to rethink their position but at least to use their minds before unleashing their instincts. Animals are all instinct. People, on the other hand, are instinct and culture, and the more the latter prevails over the former, the higher they raises themselves above the world of savagery.

I Supported Capital Punishment

In my childhood, I, like most people, supported capital punishment. This was the culture I was first introduced to in my rural environment, where ignorance prevailed at the time. A killer should be killed. I would occasionally hear expressions such as “He should be hung from his eyelids”, “He should be chopped to pieces”, or “He should be tossed into the mortar” (it was believed that in Fort La Goulette one form of execution during the Husainid dynasty,was to put the condemned into a large mortar, hammer him with the pestle, and then open the mortar from below for the pulverised corpse to fall into the ocean). Of course these images would terrify me, but I nevertheless considered the death penalty a just sentence.

This thinking stayed with me until I started to attend university in 1970. During this period, something happened that changed me and my thinking. I went to prison for the first time in February 1972 in connection with the Glorious February Student Movement. However, the short period I spent in prison, and the total isolation I experienced in my cell in the solitary confinement wing of April 9 Prison in the capital, did not enable me to learn much about the world of prisons. When I was incarcerated a second time in autumn 1974 and referred, along with my comrades in the Organization of the Tunisian Worker, to the State Security Court to be sentenced to approximately six years, there was enough time, and the circumstances were right, for me to become better acquainted and learn.

A Change of Heart

After I was transferred in late October 1974 from the State Security premises in the Ministry of Interior to April 9 Prison, I learnt from a guard that a prisoner sentenced to death had been released a few days earlier. Surprised, I asked why. The guard responded simply that, “It turns out he was not the murderer. They caught him after someone died in Mellasine. They beat him with a cane and he confessed and reconstructed [the crime] and signed [the confession].” Then he added, “A little later and they would have executed him. He spent four years sentenced to death, and the Court of Cassation confirmed the sentence. The president was going to confirm the sentence’s execution and they would hang him.”

I asked him again, what happened in the meantime? How did it emerge that the man was innocent? He responded, “Another crime happened in Mellasine, and they caught a criminal. When they investigated him, he told them he didn’t commit this new murder, but he committed the old one that our friend was accused of. We released him and told him, out, go home, you survived.” That simply, the guard summed up the matter. I returned to my cell shocked. I spent the night turning over on the esparto mat, questions assailing me from every direction. What would have happened had that person been executed before the real criminal was discovered? The state was going to destroy an innocent human soul… following a judicial ruling that seemed “concordant with the law” and was based on “serious investigations” by police, a “precise reconstruction of the crime”, and “serious judicial investigation”.

How would the chain of investigators and judges confront their conscience when they learned they had sent an innocent person to the gallows? Could this ruling be reviewed once it had been implemented? Of course not.

The State Executes a Child

My plight didn’t stop there. Rather, it increased when I encountered another troubling and terrifying case in the solitary confinement wing of the prison, where we lived one prisoner per cell. At that time, we were five political prisoners from the Organization of the Tunisian Worker and another group, namely the National Progressive Front for the Liberation of Tunisia (Ahmad al-Marghani’s group). Besides all those, there were ordinary prisoners in solitary confinement because they were being punished, they were still being investigated by the investigating judge, or they were gay. There was also a youth, we learned, that was sentenced to death in cell 4. At night, after the guards left, we would lie on our stomachs in front of our cell doors, put our mouths near the gap underneath, and talk to each other. The ordinary prisoners would allow us some time to exchange news, then all would enter the discussion to “shorten the night” and fight insomnia.

Night after night, that youngster sentenced to death would join us in conversation. His name was Hattab. He told us that he was just a few months past his 16th birthday when he was arrested on the charge of killing his mother. Hattab, a very handsome young man, left school in Manouba, as I recall, to work for a grocer and support his mother and two brothers after his father died. His mother was beautiful. She would attract attention because she was a widow, and rumors that she was unchaste emerged. These rumors reached Hattab, and suspicions began eating away at him. He asked his mother to get married and put an end to the rumors, but she refused. One time, he went to the National Guard station to tell the head officer about his suspicions, but the man scolded him and turned him away.

Gradually, Hattab began to suspect the head of the station and wonder if he, on his part, had a relationship with his mother. Why else would the man behave that way with him? “Oh Abbas [we had codenames in the wing in order to mislead the guards, and mine was ‘Abbas’], I became trapped. The eyes were staring at me and telling me my mother is a whore. I stopped sleeping at night. I left work, but it was no good. My life became hell. The world closed in on me, and I thought about only one thing: killing her. Then she would rest, and I would rest. And that’s what I did. I bought a jerry-can and lured her to a road to Fouchana. In the middle of the road, I tied her arms and legs, poured the petrol on her, and burned her while she pleaded, ‘I’m your mother!’”

Hattab would cry in agony as he narrated the details of his crime. He was detained, referred to the judiciary, and sentenced to hang. At the time, the age at which the death penalty could be applied was 16. Bourguiba was the one who, in 1968, ordered it reduced from 18 to 16 after a child murdered a European tourist. The child Hattab was the victim of one of the caprices of Bourguiba, who decided to change this age in contravention to all international laws and customs that prohibit executing children. Hattab was sentenced to death for a crime he committed while a child. The sentence in this case should not have exceeded ten years of imprisonment.

Society Condemned Hattab

Hattab would talk to me almost every night, always saying the same thing: “Oh Abbas, I was condemned by the eyes of the people. I’m a small child, and the rumors surrounded me. I didn’t find anyone to take my hand. Either I accept the situation and die inside, or I kill her and die after her. Society is harsh, Abbas. It has no mercy. People are monsters. Why didn’t the head of the station help me?” After a while, the date of Hattab’s execution arrived. Forty-three years later, the night of his execution is still stuck in my mind as if it were yesterday. We understood, Sadok Ben Mhenni and I, that Hattab’s execution was neigh from the movements of the personnel. That night I stayed awake with him very late.

Hattab was unable to sleep, so he asked me to talk to him. At some point around 3:00 AM, I heard the scratching of the keys. As usual, Hattab and I fell silent so that we didn’t fall into the guards’ trap. The door of one of the cells opened. I heard talking I couldn’t distinguish, but it was clear that a whole group of personnel was involved. Moments later, I heard Hattab’s voice: “Farewell Abbas… farewell…”. My strength vanished and I couldn’t even respond to him. I fell on the mat and cried and cried and cried. In the morning, I informed my comrades. At the time, we were gathered in cell 18. We were listening to al-Hadi al-Shanufi, who was incarcerated in the opposite cell, chant Quranic verses in tribute to Hattab, whom everyone in the wing loved and hoped would escape the noose. While in prison, we also learned that one of the daily newspapers conducted a survey, and 70% of respondents called for Hattab not to be executed.

The Responsibility of the State and Society

Hattab’s case once again revealed to me the responsibility of the state and community. Man is not created a criminal; rather, the circumstances, including the economy, society, culture, and customs and traditions, make him one. There is no crime uninfluenced by such circumstances. I say this not to justify crime but to understand it. Unfortunately, in our societies, we are accustomed to superficial thinking. We restrict responsibility to the individual so that we – and the state – can shed responsibility. Does the state not bear responsibility when it doesn’t create balanced living conditions for its citizens and they are subsequently drawn to delinquency and crime? Does the state not bear responsibility when minds are bound by archaic customs and traditions? Every widow and every divorcee is a “whore” until proven otherwise. Who doesn’t know this mentality?

Could Hattab not have escaped the noose had the head of the National Guard station helped him and paid him attention? Might he not still be alive had people taken mercy on him and ceased tormenting him with their words and looks? Could Hattab not have lived had Bourguiba, in the heat of a moment, not lowered the age at which the death penalty could be applied ? How dangerous the decisions a statesman makes in a time of anger can be, especially if that statesman is “the regime” (Bourguiba used to say, “I am the regime”, to express his absolute authority).

Is the state’s role to kill or to reform and preserve human life? Could Hattab, even if he were handed a life sentence, not have changed and reformed himself and left prison a different person?

The Law Changes to Save the Children of the Wealthy

Hattab’s case taught me another lesson. Only the poor are executed. Capital punishment too, my esteemed readers, has a class dimension. I won’t inundate you with the many examples I witnessed in prison. Rather, I will provide just one on account of its connection to Hattab’s case. In 1980, while we were in H Wing of the Civil Prison in Tunis after having spent about three years in Burj al-Rumi Prison (now Nadhour Prison), a heinous crime was committed in the capital. Late at night, three youths – the son of Bourguiba’s private doctor, the son of a consul of a sister state, and the son of a wealthy person – attacked a young man working at a petrol station in Le Bardo to steal whatever money he had from sales so that they could continue their night out. The young worker resisted them, so they gunned him down with a hunting rifle and took the money – 13 dinars, as I recall – and fled.

The three youth were arrested. Legally, the death penalty awaited them. However, following interventions, Bourguiba decided to change the law and return the age at which the death penalty could be applied to 18 years so the three boys would escape it and be sentenced as 10-year-old children. Why didn’t Bourguiba take this action for the child Hattab? Because the latter didn’t have “supports” and was one of the impoverished. The strange thing is that most defenders of capital punishment are impoverished people – people whose minds propaganda outlets manipulate, inciting them via either religion or emotion and using them against each other.

A Change of Mood Leads 11 Opponents to the Gallows

On Thursday April 17 of the same year (1980) in the same prison (April 9 Prison), we awoke in the morning and got ready to go to the prison showers. But the doors weren’t opened on time. Initially, we thought there was a search of one of the wings, which would involve many personnel. But by about 10:00 AM, we thought that something unusual was happening. At about 11:00 AM, the cell door was opened. The guard’s face was grim and his demeanor unusual. He was uncharacteristically silent, his mind astray. We passed by all the prison wings on the way to the showers and became more aware that the situation was abnormal. I remember that when we reached the showers, we saw a heap of green prison uniforms to our right. Before any of us could even comment, the prisoner charged with the showers explained, “They executed the whole Gafsa group [the armed group that entered Tunisia in January 1980]. They hung 11 souls today, the last of them after 8:00 AM”.

The shock was great. The personnel related to us the atrocities that had occurred at dawn that day. “Ahmad the Hangman” made a craft of executing his victims. On the “seventh soul”, according to one of the personnel, he stopped for a sandwich. Izzadin al-Sharif, one of the condemned, remained writhing in the noose for about 20 minutes. Some of the personnel fainted. Another became nauseous, and yet another was hospitalized by the severity of the shock.

Tahar Belkhodja, one of the ministers of interior under Bourguiba, related in his memoirs that the latter had only intended for three of the 13 sentenced to death in the Gafsa case to be executed. The sentences of the others were to be commuted to life imprisonment.

But late Palestinian president Yasser Arafat visited Bourguiba in Carthage Palace and implored him to give the group clemency and replace the death sentence with life imprisonment. Bourguiba, furious at Arafat’s interference, responded by ferrying them all to the gallows. Thus the president’s mood determines the fate of human life.

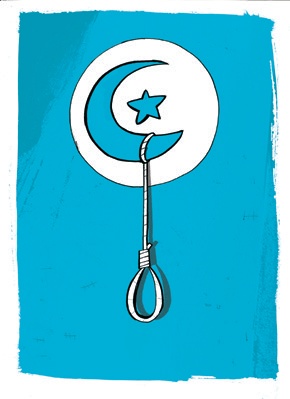

Let’s Put Away the Noose

When I left prison in 1980, I no longer had any uncertainty about the issue. I had become a firm opponent of capital punishment. When the Tunisian Workers' Communist Party (PCOT) was established in January 1986, we all agreed that its program should include abolishing the death penalty. And when the charter of the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH) was debated in the mid-1980s, the party’s members in it defended this position.

This issue is about a complete philosophy: the philosophy of reform and change versus the philosophy of punishment and retribution, the philosophy of human civilization versus the philosophy of barbarism. A civilized society is a society that abolishes capital punishment and replaces it with life imprisonment. This punishment suits murder as it takes away the offender’s liberty, but it leaves him a chance to reform. When will we put away the noose for good in Tunisia?

The Lesson

In the second half of the 1980s, the charter of the LTDH was debated. One of its clauses stipulated that capital punishment must be abolished in line with the international charters. However, the Ennahda representative opposed the clause, arguing that retribution is “a religious principle”. “What fools”, we said. Didn’t they realize that they might be the first victims of their defense of retaining the death penalty? How could they know the treacherous tides of time wouldn’t turn against them? In fact, the last group to be executed, as I recall, was the Ennahda adherents who carried out the Bab Souika operation in 1991. The leftist league members strongly opposed these sentences, as did the PCOT. The lesson of all this? When you defend a valid principle, you’re the first to benefit from it, and when you defend an incorrect stance, you could be the first to pay its price.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.