Financial Resources Key to Protection against Gender-Based Violence

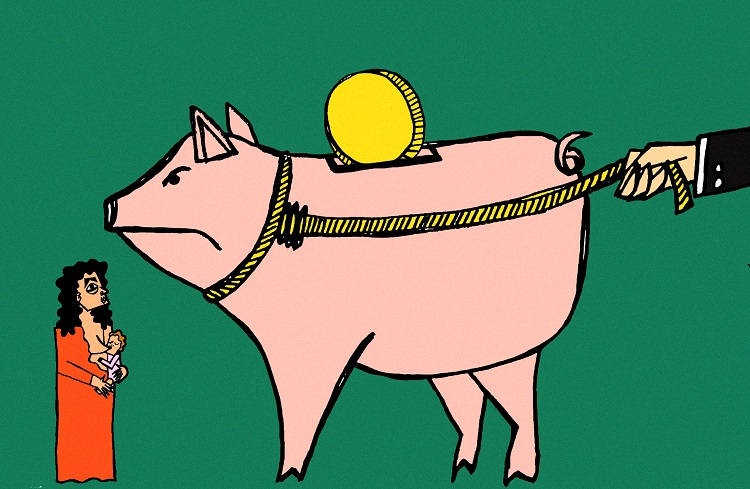

Half a decade after Lebanon adopted the Law on the Protection of Women and Family Members Against Domestic Violence, victims face new obstacles when accessing the courts to break free from domestic violence. Foremost among these is women’s lack of economic empowerment.[1] While existing protective measures go as far as removing the abuser from the marital home and lending the victim a sum of money for food, clothing, and education, the removal decision is temporary, lasting “for a period determined by the competent authority when it senses any danger to the victim”.[2] Moreover, women with no economic independence remain hostage to their abusers: if they resort to the judiciary and the marriage ends via a divorce, dissolution, or annulment decision, their husbands’ obligation of financial support ceases and they find themselves struggling to make ends meet.

Despite the importance of this issue, discussion about economically empowering women in the family context remains limited. It revolves around the amount of maintenance decided for her and occasionally addresses the importance of considering housework as a form of tangible contribution. On the other hand, rarely is the need to adopt a system of joint ownership of movable and immovable assets acquired during the marriage, or at least of the marital home, raised for discussion.[3] Similarly, there is no talk about the need to guarantee a spouse’s right to access information about all such assets.

Traditional Gender Roles Block the Economic Discussion

The near absent discussion about issues of women’s economic empowerment in the family context raises the question of why the legislature and organizations concerned with women’s rights shy away from them, especially when they, unlike many other women’s issues, do not in principle provoke any ideological conflict between liberal and conservative parties.

One of the main reasons may be that tackling financial issues within the family institution requires rethinking the social stereotypes that still govern family relationships. According to the sectarian and civil laws that address (primarily or even tangentially) marital relationships in Lebanon, the man is the head of the family and its breadwinner, while the woman is vested with raising and nurturing the children. Under these stereotypes, the economic role remains monopolized by the man.

This gender-based division of roles within the family results in the man’s control of the economic resources, especially when the woman is compelled to sacrifice her career to devote her time to housework and raising the children. Usually, this control is portrayed as legitimate: decisions about how to use money belong to the person who earns it directly, and the wife may only be involved at the husband’s exclusive discretion if he so desires.

Aspects of the implicit denial of a woman’s right to participate include not recognizing the value of her contribution via housework and raising the children and the reluctance to enshrine any right for her to access information about the assets earned during the marriage in civil laws. The persistence of this view of family relationships is further underscored by Lebanon’s social security law, which to date still includes articles that treat a woman working or assuming material responsibility for the family’s affairs as an exception. Under Article 14, of the members of a registered woman’s family, the only one to whom her coverage extends is her husband, and only if he “is at least 60 full years old or incapable of making a living because of a physical or mental disability”. Similarly, under Article 46, a husband receives family benefits “for a lawful wife who resides in the home if she does not engage in paid work”, whereas a wife receives no such benefits for a husband who does not engage in paid work.[4]

Economic Abuse as a Form of Violence

A man’s control of the economic resources within the family raises the question of economic violence as a form of domestic gender-based violence that falls within the internationally adopted definition of gender-based violence specified in General Recommendation no. 19 (“Violence against Women”) by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.[5]

Economic violence can be defined as “behaviors that control a victim’s ‘ability to acquire, use and maintain resources thus threatening her economic security and potential for self-sufficiency’”.[6] Naturally, this definition presents difficulties because it relies on “control” as one of its cornerstones, which necessitates searching for criteria for adopting the definition. In my view, economic violence requires two elements: an objective element, namely a state of economic “dependence”, and a subjective element that appears in the spouse’s behavior, namely “exploitation” of this state of dependence to obtain benefits.

This is the situation of a married woman who leaves her work to devote herself to caring for the children and marital home and who is pressured by her husband to persevere with marriage and not resort to the judiciary to dissolve it. In this regard, the proposed amendments to the domestic violence law in the draft by the joint committee of the Ministry of Justice and the organization KAFA rely on a definition of domestic violence that includes “abuse of authority within the family” resulting in economic harm and punishes such violence with “three months to three years of imprisonment and a fine ranging from the minimum wage to three times the minimum wage, or one of these two punishments, if the violence causes a family member economic harm such as deprivation of financial resources or of the family’s basic needs”.

Although these proposals aimed to amend the domestic violence law, which lacks any discussion of economic violence, we must question their effectiveness in deterring such violence in the domestic sphere given the continued reliance on the false assumption that victims of economic violence can access the judiciary. In this regard, I can only stress that Lebanese law’s lack of any serious economic empowerment for women in the family context renders the fight against economic violence futile. Perhaps it is time to discuss the means of combatting economic violence that the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women called for in its general recommendation regarding Article 16 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. These means revolve around granting women “recognition of use rights in property related to livelihood”, “compensation to provide for replacement of property-related livelihood”, “adequate housing to replace the use of the family home”, and even “the valuation of non-financial contribution to marital property subject to division, including household and family care, lost economic opportunity, tangible or intangible contribution to either spouse’s career development and other economic activity, and to the development of his or her human capital”.[7]

Toward Adopting Joint Ownership and Activating a Spouse’s Right to Access Information About Acquired Assets?

Economic violence can be addressed via two amendments to the financial relations between spouses. The first pertains to the system of movable and immovable property acquired during marriage, while the second involves developing the provisions that govern maintenance payments between spouses, particularly by granting each spouse the right to access information about the other spouse’s economic resources.

The issue of ownership of assets acquired during marriage does not fall within the recognized historical sects’ legislative and judicial power in the realm of personal status. The full bench of the Court of Cassation has deemed that the texts pertaining to the sects’ powers must be interpreted restrictively such that the judicial judiciary alone may examine spouses’ ownership of movable and immovable assets, and this must occur in accordance with civil laws.[8]

Consequently, while the adoption of an optional civil marriage law poses the issue of inference with the sects’ powers (which, in my view, is not a serious issue given that Article 9 of the Constitution protects absolute freedom of belief), the power to legislate on and adjudicate spouses’ ownership of movable and immovable assets falls exclusively within the powers of Parliament and the judicial judiciary. Hence, a civil law governing such property – one based on the principle of partnership between husband and wife as both their earnings during marriage are the product of both their contributions to the family and therefore should be divided evenly between them in the absence of a prenuptial agreement dictating otherwise – could be debated and adopted.

Some civil courts in Lebanon have applied these concepts based on civil laws of foreign countries, which must be applied to the cases brought before them because they stem from civil marriages contracted in such countries. In this regard, in a ruling issued on 10 June 2009, the 1st Chamber of the Court of First Instance in Mount Lebanon deemed that

Based on the concept of the institution of marriage, whereunder each spouse dedicates their life to the other and to the family and makes sacrifices and compromises to make their marriage work and last and preserve their family; and based on the immeasurability of the sacrifices or damages that occurred or the benefits provided; and based on the virtually constant shared responsibility in divorce cases; the wealthy party – the husband or wife – must support the other party in order for them to continue their life in an acceptable manner after the divorce. … For example, a wife leaving her work upon marriage to care for her husband, house, and children, as in the present case, or a woman not working to begin with for the same reason, falls within this [legal] characterization [and] cannot be ignored upon a divorce judgment.[9]

As for maintenance, the biggest obstacle in practice is the spouse’s lack of any paid work or, in the case of nondisclosure of the actual wage earned or of business profits, proving the spouse’s movable financial resources as the Banking Secrecy Law includes no exception for spouses. In this regard, we must question the legitimacy of withholding this information, especially given the development of exceptions to combat money laundering and tax evasion.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Lebanon, Domestic violence, Economic violence, Women

[1] Fatima Moussawi & Nasser Yassin, “Dissecting Lebanese Law 293 on Domestic Violence: Are Women Protected?”, Policy brief #5/2017, AUB Policy Institute, August 2017.

[2] Paragraphs 3 and 5 of Article 14 of Law no. 293 of 2014 on the Protection of Women and Family Members Against Domestic Violence.

[3] To the best of my knowledge, this issue has only been addressed in the context of applying foreign civil laws in the case of a civil marriage contracted outside Lebanese territory.

[4] Regarding the need to amend these articles, see the Hakkik Damanik campaign. “‘Haqqik Daman ‘Iltik’ Tastamirru li-Ta’dil al-Qawanin wa-Itlaq Musabaqa I’lamiyya ‘an Wad’ al-Mara’a”, Annahar, 23 February 2016.

[5] See, in particular, the committee’s comments on Article 16 of the agreement:

Family violence is one of the most insidious forms of violence against women. It is prevalent in all societies. Within family relationships women of all ages are subjected to violence of all kinds, including battering, rape, other forms of sexual assault, mental and other forms of violence, which are perpetuated by traditional attitudes. Lack of economic independence forces many women to stay in violent relationships. The abrogation of their family responsibilities by men can be a form of violence, and coercion. These forms of violence put women’s health at risk and impair their ability to participate in family life and public life on a basis of equality

Article 3 of the 2011 Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (a.k.a. the Istanbul Convention) also included economic violence as a form of domestic violence.

[6] Amanda M. Stylianou, “Economic Abuse Within Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of the Literature”, Violence and Victims, vol. 33, is. 1, 2018.

[7] General recommendation of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women regarding Article 16 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

[8] Dr. Sami Badih Mansour, Dr. Nasri Antoine Diab, Dr. Abdou Jameel Ghasoub, al-Qanun al-Duwaliyy al-Khass: Tanazu’ al-Ikhtisas al-Tashri’iyy, p. 481; P. Catala & A. Gervais, Le droit libanais, T.I.L.G.D.J., 1963, p. 56; Decision no. 8/98, dated 23 January 1998, Civil Cassation, full bench, published on the Cassandre database; Decision no. 63/2014, dated 30 June 2014, Civil Cassation, full bench, published on the Cassandre database.

[9] Ruling no. 42, issued on 10 June 2009, published in al-‘Adl, 2010, is. 2. In the same vein, see Decision no. 159/2018, dated 27 June 2018, issued by the Civil Court of Appeal in Mount Lebanon, 13th Chamber, and published in the Cassandre database. Regarding the application of foreign law requiring the division of joint property, see Ruling no. 59/2018, dated 27 February 2018, issued by the Civil Court of First Instance in Jdeidet al-Matn, Personal Status Chamber, unpublished. This ruling ordered the division of joint assets and application of the law of the state of Virginia.

In this regard, note also Article 74 of the Orthodox sect’s personal status law, which stipulates that “the court may, in the case that the woman is in financial straits, order the man to pay her a monetary sum for her to confront her new situation after the breakup of the marriage”, and the decisions issued by the Orthodox Court of First Instance in Mount Lebanon on 22 March 2010, 30 June 2001, and 15 November 2010, which compelled the husband to pay the wife a monetary sum on the basis of this article.