Egypt’s September 20 Protests: Towards Change or More Repression?

Egypt is currently experiencing a state of perplexing political confusion that could change the current political landscape. On 20 September 2019, after years of repression, public squares in a number of governorates, particularly Tahrir Square, witnessed hundreds of protesters demanding that President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi leave office. Citizens shouted slogans such as, “The people want to topple the regime”, “Sisi, leave”, “Don’t fear, Balaha* must go”, and “Sustenance, freedom, social justice” as they tore up pro-Sisi pictures and signboards distributed throughout the streets in a spectacle reminiscent of the beginning of the January 25 Revolution, when pictures of then-president Hosni Mubarak were torn up. These protests came in response to a call made on social media by actor and construction contractor Mohamad Ali.[1] He asked Egyptians to take to the streets in opposition to the corruption of the president and his family and the squandering of state financial resources on the construction of presidential palaces and retreats. The turnout to the protests, which continue to this day in some areas such as Suez Governorate and el-Mahalla el-Kubra, prompted a reassessment of political affairs and an attempt to understand their course amid the confusion and obscuration. On social media, some tied the rapid turnout to the protests after Ali’s call to the existence of political disputes between the state’s sovereign bodies and undisclosed Armed Forces leaders over whether the president should remain in office. This was backed up by the fact that some protesters’ testimonies and videos on social media indicate that the security forces used little repression against the protesters, going against the norm since Sisi took over the country’s administration. Others considered that unlikely, and explained the events by saying that the people are fed up. This article sheds light on the role of social media in breaking the barrier of fear that citizens faced after years of silence, particularly because the calls for protest were made via social media and the protests were then covered using it. It will also address how the state’s web and media brigades responded to contain the situation and reinforce Sisi’s public image.

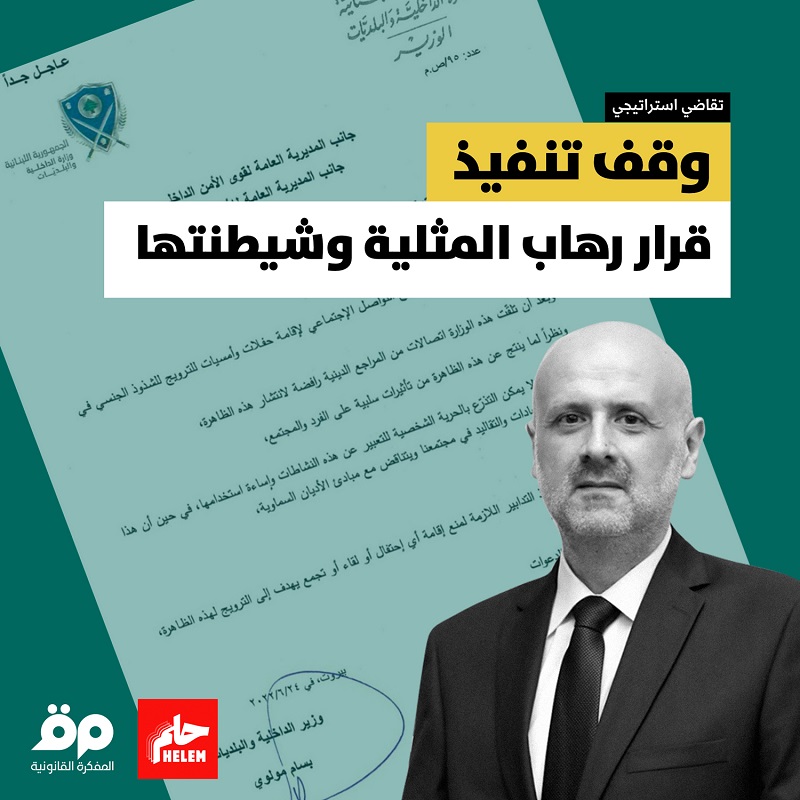

The Impact of Social Media in Mobilizing the Masses and the State Agencies’ Responses

The events began unfolding after Ali posted his first video on social media, in which he spoke about the corruption of Armed Forces leaders and the embroilment of the president and his family in squandering public funds on the construction of presidential palaces and fancy resorts. This video was shared widely among social media users, and many reposted it on their personal pages. Consequently, the security agencies put pressure on Facebook and Twitter to delete Ali’s account.[2] Ali then posted a series of videos revealing the corruption inside the Armed Forces and presidential establishment, which received more than a million views. This opened the door for many activists and opposition figures living abroad to post videos analyzing and critiquing the president’s policies and the Egyptian army’s embroilment in corruption cases since the protests of 30 June 2013, which led to Sisi’s presidency. Meanwhile, political activist Wael Ghonim appeared in a series of similar videos discussing the corruption of General Intelligence generals during and after the Egyptian Revolution and of Sisi’s son Mahmoud, who received an exceptional promotion to the rank of brigadier general and became vice president of General Intelligence.[3] Amid this torrent of different videos and opinions, citizens began reposting leaked audio of a conversation between Sisi and then-director of the president’s office Major General Abbas Kamel, as well as a video clip of Major General Kamel al-Wazir, currently the minister of transport, talking to the people of Sinai and consenting to “smuggling and money laundering” on the condition that the armed forces receive a share of the smuggling proceeds.[4]

On the other hand, the security agencies handled the events in a traditional manner. The web brigades began recirculating videos showing the president’s human side, such as clips of his surprise visits to military checkpoints and of him with the families of people killed. They also posted patriotic songs and accused the Muslim Brotherhood and its media agencies of creating chaos to destabilize the nation and fabricating facts via fake videos totally divorced from reality. Media figures began denying the existence of financial corruption within the military and presidential establishments. Egyptian actors were apparently asked to post a video supporting Sisi in combatting terrorism and analytical videos countering the accusations by Ali and social media activists. Furthermore, the latest Youth Conference discussed the effect that spreading lies has on the state in light of fourth-generation warfare and how technology and new media can facilitate terrorist operations.[5] How video content can be faked to fabricate facts using technology was also explained technically. However, the president’s admission that hundreds of millions were squandered on unnecessary projects such as presidential palaces helped increase Ali’s credibility. Ali responded with the Arabic hashtag “That’s enough Sisi!” and a call to protest on Friday, September 20, to topple Sisi’s regime. The web brigades succeeded in deleting the hashtag from Twitter and replacing it with the hashtag “We’re with you Sisi”.[6] But as the citizens took to the streets, the media agencies began returning to the strategy of misleading public opinion and denying the fact that citizens were protesting on a national level. This they did by showing Tahrir Square empty on a government channel and by propagating the idea that the citizens were in the streets celebrating their team’s victory in a football match.

The Security Forces and Security Apparatuses’ Handling of the Situation

According to eyewitnesses, the security forces’ involvement differed greatly from the norm, with their approach differing from region to region. One video showed an officer ordering Central Security personnel not to attack citizens, while another showed security personnel attacking protesters with force and dispersing them with tear gas. The security forces arrested hundreds of protesters across the various governorates. Lawyers stated that the security agencies sorted arrestees into two groups in the detention facilities, releasing those with no record of activism or political affiliation while charging those with political affiliations or a political opinion with protesting and assembly.[7] After the September 20 protests, the security forces also began intensifying state-of-emergency measures and conducting arrest campaigns in all governorates, especially around Tahrir Square and central Cairo, by stopping and searching passers-by and examining their phones for evidence of affiliation with a school of political thought.

At dawn on September 23, the State Security Prosecution began interrogating 370 accused persons from all governorates in State Security Case no. 1338 of 2019. They faced charges of collaboration with a terrorist group in executing its plans, posting and spreading false news on social media, misusing social media, and protesting without permission. Meanwhile, the security forces began arresting political activists. Examples include rights lawyer and activist Mahienour el-Massry after she attended the interrogations of the accused in the State Security Prosecution premises, the brother of political activist Wael Ghonim, Vice President of the Socialist Popular Alliance Party Abd al-Naser Ismail, and Vice President of the Dignity Party Abd al-Aziz al-Husseini.[8]

After the September 20 protests, Ali again took to social media to thank citizens for responding to the calls to take to the streets, to thank the army and police for not using violence against the protesters, and to call again for protests in all of Egypt’s squares on Friday, September 27.

However, the escalation from the security agencies is ongoing. They are continuing their widespread campaign of arrests in all governorates and have cut off Messenger in Egypt to block Ali’s videos and get control of the situation, perhaps in preparation for cutting off all internet services should they fail to get control soon.

Conclusion

Certainly, the September 20 protests achieved some gains that mark the beginning of a new popular movement as they managed to break down the barrier of citizens’ fear of taking to the public squares and demanding the regime’s fall once again after more than five years of repression. The media agencies and the state’s web brigades failed to intimidate the citizens into not taking to the squares using terrorism arguments and patriotic rhetoric. It is also certain that Ali’s videos about corruption cases involving the president and his family had a large impact on the masses’ consciousness of facts they were already aware of but never dared speak about or confirm. Ali succeeded in rallying many citizens because he spoke of corruption and theft of public funds by institutions and individuals to build palaces and resorts and buy fancy cars at a time when the president is constantly talking about insufficient financial resources and the state’s poverty. There may be a number of leaders and generals who are not enthusiastic about having the president remain in office, but we do not know the true reasons why. It may be because the president’s policies have made the army’s investments public gossip, because these leaders have been deprived of privileges now enjoyed by the president’s loyalists, or because of public interest considerations.

Whatever the case, social media has begun spreading the people’s demands should attempts to remove the president succeed. They consist of releasing all detainees, investigating corruption incidents and the squandering of public funds, abolishing the recent constitutional amendments, and reviewing economic policies and prohibiting policies of monopolization. But, if these attempts fail, the security services are expected to increase repression, and the president may decide to arrest some former Armed Forces leaders or replace some current ones.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

*Translator’s note: “Balaha” is a nickname Egyptians have adopted for Sisi, likening his appearance to a raw date.

Keywords: Egypt, Protest, Corruption, Sisi

[1] Amira Mousa, “Fi Muwajahat al-Fasad: Kayfa Tafa’alat al-Dawla al-Misriyya wa-l-I’lam ma’a al-Ittihamat al-Akhira bi-l-Fasad?”, The Legal Agenda, 22 September 2019.

[2] “Block Block Block … Twitter Yu’aqibu al-Muqawil al-Harib Muhammad ‘Ali bi-Sabab al-Tazyif wa-l-Kidhb”, Sout Alomma, 21 September 2019.

[3] Muhammad Mughawir, “Abna’ al-Sisi Yasna’una Imbraturiyya bi-l-Raqaba wa-l-Mukhabarat”, Arabi21News, 22 July 2018.

[4] Video posted on YouTube titled “Kamil al-Wazir Ra’is al-Hay’a al-Handasiyya Yuwafiqu ‘ala al-Tahrib wa-Ghasil al-Amwal fi Mashru’at al-Jaysh”, 24 April, 2016.

[5] Video posted on YouTube titled “Kalimat al-Mukhrij Tamir al-Khashshab Dimna Jalsat Ta’thir al-Akadhib ‘ala al-Dawla fi Daw’ Hurub al-Jil al-Rabi’”, 14 September 2019.

[6] “Harb Hashtagat fi Misr wa-Sirr Ikhtifa’ Kifaya Baqa Ya Sisi”, Alhurra, 18 September 2019.

[7] “Intifadat Sibtambir li-Ifraj ‘an al-‘Asharat wa-Ihtijaj Akharin bi-Misr”, Arabi21News, 21 September 2019.

[8] “’Ajil al-Qabd ‘ala al-Nashita al-Huquqiyya Mahienour el-Massry”, cairo24, 22 September 2019.