Egypt’s New Parliamentary Elections Law: A Blow to the Multiparty System and Unequal Representation of Citizens

On June 5, 2014, former Egyptian President Adly Mansour issued the parliamentary election law that will regulate the upcoming elections of the House of Representatives. Notably, the law was issued without the benefit of a public debate, and without being presented to political parties for feedback. It was issued after the announcement of presidential election results, a mere three days before Mansour handed over power to current President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. This raises the question of whether Mansour took it upon himself to face anticipated criticisms of the law, as a way of shielding el-Sisi from accusations of undermining party life in Egypt.

The next House of Representatives is billed as one of the most important legislative bodies in Egyptian history, as it will be required to issue a set of crucial legislation – most notably, supplementary laws to the Constitution starting with the law regulating the building of churches.[1] It is also expected to issue a law organizing the rules for assigning judges and members of judicial bodies and organizations, with the aim of cancelling assignments to non-judicial bodies and institutions.[2] Moreover, according to Article 156 of the Constitution, laws that were issued during the previous period must be presented to the new House of Representatives, which will confirm or repeal them. This could be a significant opportunity to reconsider laws, such as the protest law, that caused controversy in the previous period.

The Individual Candidate System and the System of Absolute Closed Lists: Undermining Political Party Life in Egypt

Does the law ensure the representation of all segments of society in the House of Representatives, making it fit to implement a legislative agenda of the utmost importance? Does it achieve appropriate representation for women, minorities, and marginalized groups?

The new law states that Parliament is made up of 540 members, of whom 420 (over 70%) are elected according to an individual candidate system, and 120 are elected through absolute closed lists.[3] “Absolute closed lists” means that the list of candidates that gains the absolute majority of votes wins all the seats in its electoral district. It differs from the proportional list system used in Egypt’s 2012 elections, whereby each list gains a certain number of seats according to the proportion of votes it received. The latter model, known as the system of proportional closed lists, achieves representation for all parties and political factions according to the percentage of the vote they attain in elections. This is in contrast to the model of absolute closed lists which promotes a system that favors the majority, without ensuring appropriate representation of all parties and political factions. In order to avoid constitutional challenges (as happened with the previous election law),[4] the new law stipulates that parties and independents are both entitled to run for seats allocated to the individual candidate system, as well as those allocated to the closed list system.[5]

Various Egyptian political parties have objected to the law. Hala Shukrallah, president of the Egyptian Constitution Party, commented on the law by describing it as “undermining the political blocs that are capable of holding the government accountable and monitoring its performance, as it undermines party life in Egypt and it encourages filling the next House of Representatives with businessmen”.[6] Hussein Abdel-Razek, leader of the National Progressive Unionist Party, described the closed list system as “the worst list system in the world”.[7]

It is worth mentioning that Article 5 of the current Egyptian Constitution specifies that “the political system is based on political and partisan pluralism”. In the coming days, will we see a challenge to the unconstitutional nature of the parliamentary election law and its overthrow of political party life in Egypt?

Unfair Representation for Women, Minorities, and Marginalized Groups

Firstly, The 2014 Constitution did not specify a “quota” for workers and farmers. Whereas in the past, Egyptian constitutions had specified that half the seats in parliament should go to such groups. The quota dates back to the era of late President Gamal Abdel Nasser. In the 2014 Constitution, Article 243 only stipulates that the state must “endeavor that workers and farmers be appropriately represented in the first House of Representatives to be elected” following the Constitution’s approval.

Secondly, the proposed system offers guarantees for a number of categories for seats reserved under the list system, but not for the individual candidate seats. Thus, out of the 120 seats determined by the list system, 24 are allocated to Christians, 16 for workers and farmers, 16 for youth, 8 for persons with disabilities, and 8 for Egyptians living abroad. Women are allocated 56 seats. They include seats occupied by women in the above categories. Article 27 of the law also stipulates that half of the seats that the president appoints (that is, 13 or 14) must be reserved for women.

Consequently, the legislature has designated very few seats for these categories [overall], which is not in accordance with the proportions of society they represent. This cannot be considered “appropriate representation” of these groups, as required by the Constitution.

It is also worth mentioning that the NGO Nazra for Feminist Studies, as well as other parties and organizations, had rejected the initial draft of the law before it was passed. They demanded the implementation of a different system that was 50% individual candidate, and 50% proportional closed lists, wherein parity was applied for individual seats so that women would obtain 50% of them; and whereby lists were arranged in order by gender (that is, man, woman, man, woman, etc.), in order to guarantee fair representation of women in the next parliament.[8] As has been made clear, this suggestion was neither responded to nor resorted to, and the law as passed is oppressive to Egyptian women.

Egyptians Living Abroad

The law stipulates, for the first time, the representation of Egyptians abroad through 8 seats set out in the list system, as explained above. ِEgyptian law has recognized Egyptians living abroad as follows: “all those who make their regular residence outside of the Republic of Egypt on a permanent basis, and who have attained permission to reside permanently in a foreign country or to stay abroad for a period of time for no less than 10 years preceding the day of opening candidacy registration. In applying the provisions of this law, students and persons seconded or deputized abroad are not counted among those living abroad”.

Article 8 of the law also stipulates that candidates for membership in the House of Representatives must enjoy “solely Egyptian citizenship”, thereby preventing dual citizens from running for office. Some consider this to be in conflict with the definition specified for Egyptians living abroad, as if a person residing abroad for more than 10 years acquires the nationality of the country in which he is residing, then he would thus become a dual citizen.[9]

In addition, the 8 seats cannot be considered appropriate representation for Egyptians abroad. The law does not ensure equal representation of all Egyptians living abroad. It does not, for example, designate a number of seats for the representation of Egyptians in each foreign country or region, in accordance with the number of Egyptians living there in order to guarantee their equal representation.

Increasing the Mandatory Deposit: Preventing Those with Limited Income From Running for Office

Article 4 of the Egyptian Constitution states that “Sovereignty belongs only to the people, who shall exercise and protect it. The people are the source of powers, and safeguard their national unity that is based on the principles of equality, justice and equal opportunities among all citizens”. However, in violation of the principle of equal opportunities, Article 10 of the parliamentary elections law requires candidates who wish to run for office to deposit a sum of EGP 3,000 [US$420]. This amount is not excessive, but it is not a small sum either. The law thus places limitations on the poor and persons with limited income regarding their ability to run as candidates.

Do the lawmakers then wish to advantage a particular socioeconomic class (namely, the upper middle class and the wealthy, who can afford to pay this sum), to the exclusion of others (namely those with limited income and the poor) who represent a larger proportion of the Egyptian people?

Regulating the President’s Appointments of Members of the House of Representatives: Learning from the Mubarak Era

According to the 1971 Constitution, as well as a constitutional amendment made in March 2011, the president was given the right to appoint 10 members of the People’s Assembly, and a third of the members of the Shura Council.[10][11] The Shura Council was eliminated with the new Constitution, which states in Article 102 that the president has the right to appoint 5% of the House of Representatives (that is, 27 seats).

However, Article 27 of the new parliamentary election law sets new regulations for these appointments. First, the article states that half of these seats (13 or 14) must go to women. It further specifies that the president must use this portion “for the representation of experts, those who have achieved scholarly and practical accomplishments in various fields, and groups whose representation in the House of Representatives is specified in the provisions of Articles 243 and 244 of the Constitution”, and in light of nominations made by a number of qualified councils.[12] This lessens the possibility of reliance on patronage and the appointment of relatives.

In addition, the article restricts appointments in other ways, specifying that:

whoever is appointed meets the necessary conditions of membership in the House of Representatives;

no president may appoint “a number of persons from the same political party that would lead to a change in the parliamentary majority in the House”;

the president shall “not appoint a member of the party that the president belonged to prior to taking the office of president”; and

“that he not appoint a person who ran for the House of Representatives in the same election season and lost”.

Conclusion

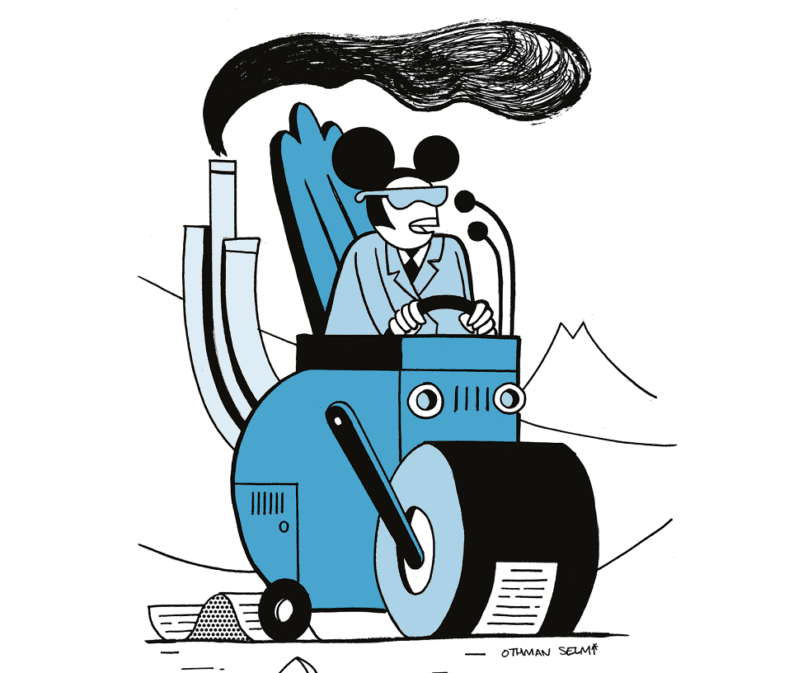

Based on the law discussed, lawmakers appear to have designed a system that favors the majority and the interests of capital, without guaranteeing appropriate representation of various groups of the [Egyptian] people. They employed one of the most important reforms of the revolution (the introduction of the proportional list system in election law). However, only after altering it in a manner that would see Egypt regress into conditions similar to those under the Mubarak era when big business dominated and a single faction monopolized power to the exclusion of others. Thus, it is difficult for the law to contribute to the building of a sound political party life in Egypt – which is one of the fundamental components of ensuring the peaceful rotation of power.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

__________

[1] Article 235 of the Constitution.

[2] Article 239 of the Constitution.

[3] Article 1 of the election law.

[4] On June 14, 2014, the Supreme Constitutional Court issued a ruling that the law regarding the People’s Assembly was unconstitutional for a number of reasons, including the right of parties to run as candidates for seats elected via the individual candidate system alongside independents, while restricting the seats elected via the list system to party candidates only.

[5] Article 3 of the election law.

[6] See the website of Shorouk newspaper, June 8, 2014.

[7] See the website of Shorouk newspaper, June 2, 2014.

[8] See the website of Nazra for Feminist Studies, May 25, 2014.

[9] See the statements of the Free Egyptians Party on this topic.

[10] See Articles 87 and 197 of the 1971 Constitution.

[11] See Articles 32 and 25 of the Constitutional Declaration issued in March 2011.

[12] These categories are: workers and farmers, Christians, persons with disabilities, and Egyptians living abroad.