Decision: In the name of the Lebanese people

|

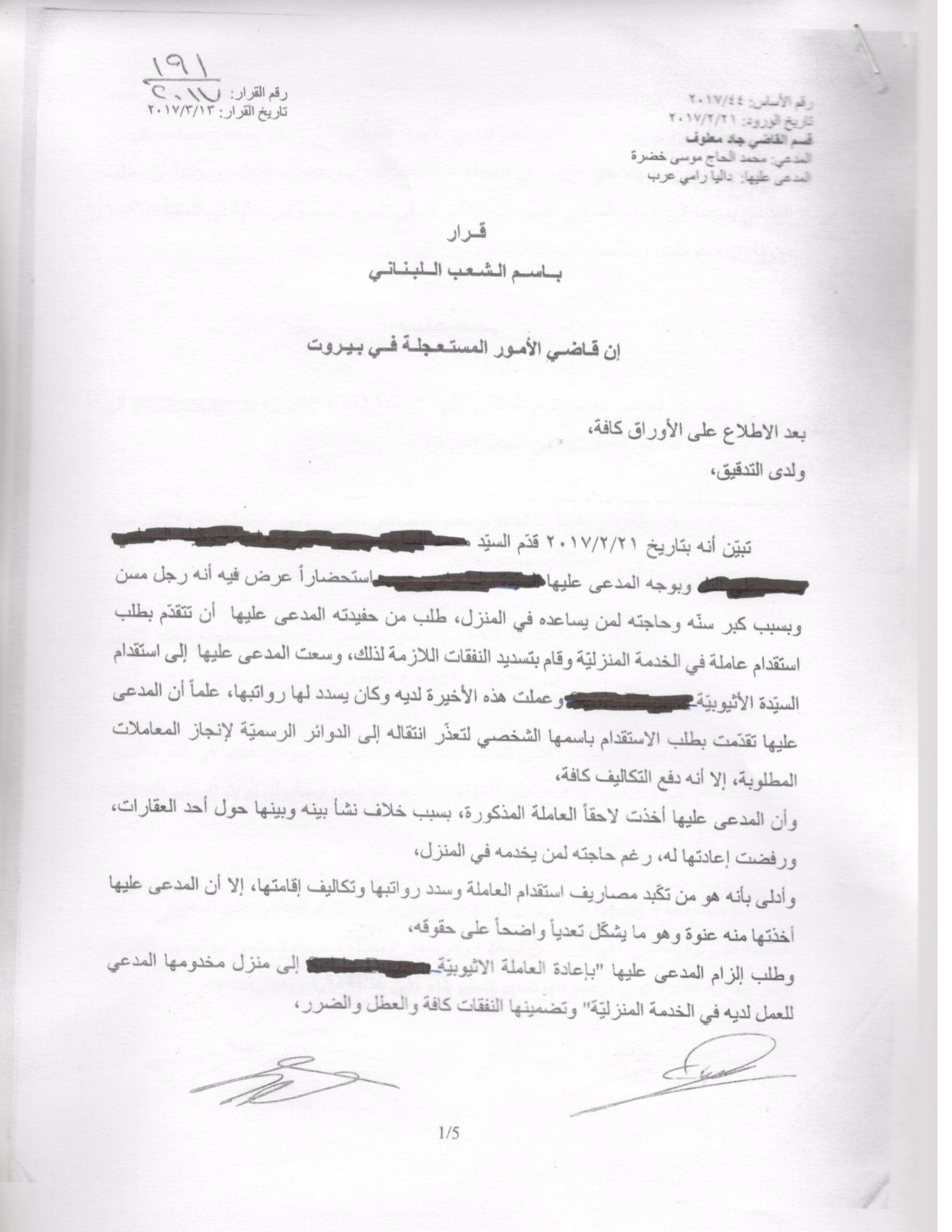

Base No.: 44/2017 Date of Receipt: February 12, 2017 Department of Judge: Jad Maalouf Plaintiff: [name redacted] Defendant: [name redacted]

|

Decision No.: 191/2017 Decision Date: March 13, 2017 |

Decision:

In the name of the Lebanese people

The Summary Affairs Judge in Beirut

After reviewing all documents,

And upon careful examination,

It is evident that on February 21, 2017, Mr. [name redacted] filed against defendant [name redacted] an arraignment wherein he set forth that he is an elderly man, and because of his advanced age and his need for someone to assist him in the home, he asked his granddaughter, the defendant, to file an application to import [istiqdam] a domestic worker, and [he] paid the associated expenses. The defendant imported the Ethiopian Ms. [name redacted], and the latter worked for him [i.e., the plaintiff] and he paid her wages. The defendant filed the import application in her own name because it was impracticable for him [i.e., the plaintiff] to travel to government departments to complete the required transactions. However, he paid all the expenses.

[It is also evident] that the defendant later took said worker because of an argument between him [i.e., the plaintiff] and her about some real estate. She refused to return [the worker] to him even though he needed someone to attend to him at home.

He stated that he is the one who bore the expenses of importing the worker and paid her wages and accommodation costs, but the defendant forcefully took her from him, which constitutes a clear encroachment on his rights.

He requested that the defendant be compelled “to return the Ethiopian worker [name redacted] to the home of her employer, the plaintiff, to work for him in domestic service”, and for her to cover all expenses and damages.

It is also evident that in the hearing convened on March 3, 2012, the defendant’s lawyer Muhammad al-Maghribi pled, asking for the claim to be rejected because the summary affairs judge lacks jurisdiction, and both the plaintiff and defendant lack standing and interest as the worker had left the home and the country. [Said lawyer] stressed that the plaintiff’s request aimed to force the defendant to participate in the crime stipulated in Article 568-1* of the Penal Code. The trial was duly concluded.

On That Basis,

Whereas the plaintiff requests that the defendant be compelled “to return the Ethiopian worker [name redacted] to the home of her employer, the plaintiff, to work for him in domestic service”;

Whereas the defendant requests that the claim be rejected because the summary affairs judge lacks jurisdiction, because both parties lack standing and interest, and because it contravenes public order;

Whereas the second paragraph of Article 579 of the Code of Civil Procedure empowers the summary affairs judge to take measures that put an end to a clear encroachment on legitimate rights or circumstances;

Whereas the basis of the summary affairs judge’s jurisdiction when taking the measures stipulated in said paragraph is the certainty of an encroachment on legitimate rights or circumstances, even if the two conditions of urgency and not addressing the basis [of the dispute] are not met;

Whereas there is no doubt that the present case –which aims to compel the defendant to return a domestic worker to the plaintiff– is unique and raises a key issue that must be addressed, namely the acceptability of a claim whose subject matter is the handover of a human being on the basis of a financial and contractual relationship;

Whereas the seventh article of the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery adopted by a Conference of Plenipotentiaries convened by Economic and Social Council Resolution 608(XXI) of April 30, 1956, stipulates that “slavery” means, as defined in the Slavery Convention of 1926, the status or condition of a person over whom the powers stemming from the right of ownership are exercised, and “slave” means a person in such condition or status;

Whereas it follows from the above that practicing one of the facets of the right of ownership over any human being is a form of modern enslavement;

Whereas although Lebanon has not signed or ratified said Convention, it may seek guidance from the definition specified above. Note also that Lebanon is in any case bound by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which stated in its first article that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, and they are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Similarly, in its fourth article it stipulated that no one shall be held in slavery or servitude and slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms [sic. awda’ihima];

[Lebanon is also bound by] the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which stipulated in its eighth article that no one shall be held in slavery, slavery and the slave-trade in all their forms shall be prohibited, and no one shall be held in servitude;

Whereas subsequently, it need not be said that Lebanon rejects enslavement in all its direct or indirect forms, where enslavement means the status or condition of any person over whom the powers stemming from the right of ownership are exercised;

Whereby it must also be noted that the manner of dealing with the matter that appeared in this claim targets –especially and even exclusively– foreign [female] domestic workers. It must be clearly confronted because of, firstly, the state’s commitment under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes, or on stereotyped roles for men and women, as set out in said Convention’s fifth article;

Secondly, [this way of doing dealings must be confronted] because of the state’s commitment under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination to condemn racial discrimination and undertake to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms, and promoting understanding among all races; to engage in no act or practice of racial discrimination against persons, groups of persons, or institutions; to ensure that all public authorities and public institutions, national and local, shall act in conformity with this obligation; and to not sponsor, defend, or support racial discrimination by any persons or organizations, as set out in said Convention’s second article;

Whereas upon returning to the subject matter of the present claim, it is evident that irrespective of the phrasing used and portrayal adopted, it [i.e., the claim] actually aims to compel the defendant to hand over a person to the plaintiff. It thereby appears to aim to obtain a judicial ruling to transfer “possession” of a person from the defendant to the plaintiff. This is unacceptable because of the various aforementioned principles and texts and because it would involve considering the person concerned to be the subject of an ownership right, which constitutes a form of modern enslavement that the judiciary cannot partake in or protect. It must therefore not accept the claim;

Whereas upon arriving at this conclusion, all additional and contrary causes and claims must be dismissed either because they were implicitly addressed in the explanation set out above or because they lack merit.

Therefore,

Decides:

To not accept the claim and for the plaintiff to cover all expenses.

Ruling with immediate effect issued and made viewable to the public in Beirut

on March 13, 2017.

|

Clerk [Signature]

|

Judge Jad Maalouf [Signature] |

This document is an edited translation from Arabic.

*Translator’s Note: the intended reference may be Article 586(1) of the Penal Code, which pertains to human trafficking. No article numbered 568-1 exists and Article 568 appears to be unrelated to the case.

Mapped through:

Articles, Asylum, Migration and Human Trafficking, Lebanon

Related Articles