Cooperativism in Tunisian High Court Jurisprudence: Misleading and Betraying the President

In mid–1969, Tunisia witnessed a severe socioeconomic crisis stemming from the failure of cooperativism, which late President Habib Bourguiba had publicly adopted six years earlier as his socioeconomic policy for advancing Tunisia and overcoming underdevelopment. At that point, Bourguiba rushed to distance himself from the cooperativism policy. However, his discourse was not enough to deflect the political accusation that he alone was constitutionally responsible for the failure of one of his policies given that the 1959 Constitution vested him with executive authority and, by extension, setting public policy, overseeing its implementation, and choosing the members of his government. Yet this was not the position of the state and its representatives at the time for two reasons. Firstly, Bourguiba had not actually been the one managing the economic portfolio. Rather, Ahmed Ben Salah had engineered the experiment and, throughout its term, occupied the important economic ministerial positions, wherein he made decisions independently.[1] Secondly, the prevailing political culture rejected the mere thought of holding the nation’s leader accountable, even for a failure to monitor the performance of his “arms”, as the top officials were called at the time. The constitutional predicament appeared serious, so prudence was needed when devising the appropriate remedy.

Ben Salah, Wait at Home While We Make Arrangements for You

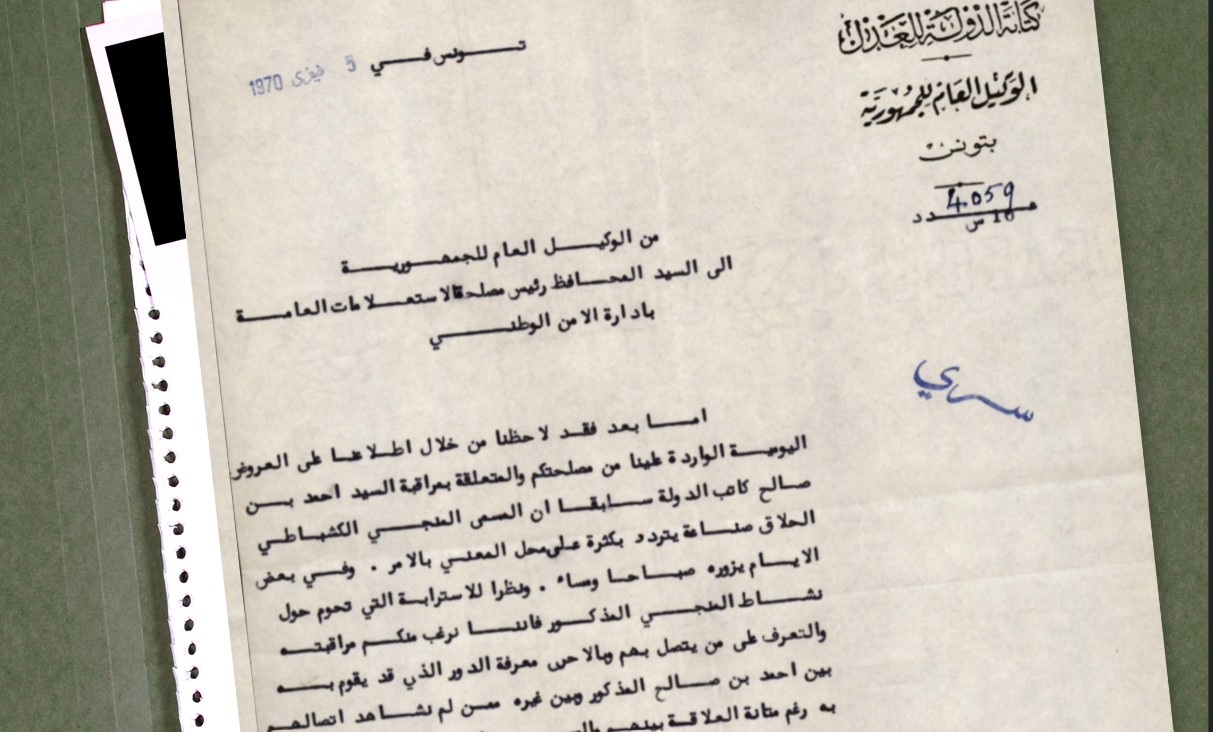

By the end of 4 November 1969, Ben Salah had been removed from all his functions. From that day, the governmental and semi-governmental media launched into discussion about his crimes against Tunisia, the tragedies caused by his abuse of power, and Bourguiba’s love for his people and regret for what had happened to it. At that point, everybody knew that Ben Salahwould end up in prison. However, the judicial prosecutions did not reach him for over three months, during which he was merely surveilled by Intelligence Department agents. Meanwhile, everyone who entered his home or called him or his wife wrote a detailed report about him and submitted it to the top security and judicial authorities in anticipation of the decisive moment wherein the Supreme Court – which could exonerate the president without asking any questions and without him standing accused – would intervene.[2]

The Supreme Court Law: Tailored Legislation

The Parliamentary Investigation Committee, which examined the excesses that had accompanied the cooperative experiment in its report dated 29 December 1969, called for the Supreme Court to take up the investigations. Because the constitutional text establishing the court required a law governing its procedure and powers that was yet to be issued, the Ministry of Justice undertook to submit a bill for this law to Parliament. The bill was introduced less than two months later. Minister of Justice Mohamed Snoussi justified the bill’s hasty drafting on the basis that the constitutional institutions needed to be activated, without hiding that the court would soon play a role trying Ben Salah.[3] He jokingly reminded the MPs that when the National Constituent Assembly had debated over the Supreme Court on 23 October 1958, Ben Salah had intervened to express his surprise and opposition to the idea, claiming that the court was unnecessary.[4] Snoussi was thankful that Ben Salah’s stance had found no support among his colleagues and marveled that the person who had opposed the court would be the first to be tried before it.

Premeditated Political Criminalization

The MPs debated the bill on 31 March 1970. Those who spoke in the session eagerly registered their enthusiasm for the anticipated trial, perhaps in an attempt to disavow their presumed connections to the man whose economic plan they had roamed the countryside and cities supporting and to whom they had boasted about being close. The bill deemed the act of a member of government “intentionally misleading the head of state and thus undermining the nation’s supreme interest” high treason punishable with the penalty stipulated “in the Penal Code for crimes against state security, accompanied if necessary by deprivation from civil and political rights”. It also vested the president of the republic with the power to appoint the Supreme Court’s judge members and issue permission to conduct investigations.[5] Hence, the law made the president the one to effect accountability and deemed his errors to stem not from his action but from deception that prevented him from making the correct choice. This new distribution of responsibility was what Bourguiba needed to free himself fromof the burden of the experiment. He had become a victim of deception who deserved to be avenged.

The day after Parliament’s approval, the Supreme Court Law was issued in the official gazette. Two days later, the court’s judge members were appointed via individual presidential orders, and its MP members were elected by their colleagues. The president ordered the prosecution of Ben Salah and eight senior officials in the cooperative era before the court, the former for high treason and the latter as his accomplices.[6]

A Hasty Trial: The Judiciary Convicts the President’s Deceiver

The investigating judge placed the defendants in prison as soon as they appeared before him. His investigation took one month and ten days and ultimately substantiated that the principal defendant had manipulated the leader’s trust. According to the decision concluding the investigation, it showed that Ben Salah had a history of rioting and sowing strife. He had become the general secretary of the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) after the assassination of its leader Farhat Hached. He “brought his way of disorder and chaos into that organization”, pursuing “personal ambition and goals imbued with destructive, foreign-inspired principles that he learned from extreme leftist elements”, and was consequently removed from the position of responsibility. Yet “he did not turn a hair, anticipating opportunities to recover his standing in Tunisian society and continue his programs and schemes to reach his goals, and displaying regret, repentance, and a readiness to serve the state”. Hence, “the head of state saw in him promise for the nation and, in 1957, assigned him a responsibility in government”. Then, in 1961, the president “elected him to the office of state secretary for planning, believing that Ahmed Ben Salah, known for his activity and trusted in his devotion, would be faithful to the principles of the party and state and its plans”. Having explained how the leader fell victim to his own kindness and trust in Ben Salah, the investigator’s work proceeded to show how the latter was an expert conspirator.

To do so, the investigation work returned to Ben Salah’s unionist history. From the preamble of the UGTT economic report that he had drafted and wherein he preached cooperativism, it quoted his statement that cooperativism, as a program, was “not just theory but a tool for struggle and should be put into practice”. This was in and of itself sufficient evidence that cooperativism was a conspiracy whereby Ben Salah sought to “control the economic apparatus absolutely”. He “installed his followers in decision-making positions and insisted on keeping them there despite knowing their nefarious behavior and despite the recommendations he received from the head of state to remove them after he [i.e. the head of state] ascertained their tampering and misconduct”, all in order to “settle on the throne of influence”. Once Ben Salah achieved his goal, “he neglected and trampled the principles of the party, overstepped the government’s instructions, and betrayed the president’s trust”. As soon as the leader realized, he removed Ben Salah and effected accountability, and it was in this process that the investigator saw sufficient evidence to level charges and refer the defendant and his accomplices to the court.

Criminal Law Retroactivity: Matter of Perspective When Combatting Treason

The law issued after the cooperative experiment ended criminalized “misleading the head of state” and punished whomever does so with the sentences stipulated for crimes against internal state security. The inclusion of this newly introduced crime among the charges leveled at Ben Salah and company raised the question of whether the procedures of his trial respected the principle of the non-retroactivity of criminal law. The court president addressed this question from its first sessions. After reviewing the decision concluding the investigation, he recited a text – unrelated to the case – addressing supreme courts in comparable legislations. Rebutting the potential argument that the principle of nonretroactivity must be respected, the text stated, “This principle has today come under examination, and criminal law scholars now question its validity because it puts the individual before society and takes individual freedom too far. This principle was developed in an era when it was justified by the excess of authority occurring and is no longer justified today because circumstances have changed. Consequently, it has become an obstacle to protecting public interest, not just national but in many instances global”. The judge finished by reciting a report contending that the Supreme Court Law complied with the principle because it merely explained criminal acts without imposing new punishments not already in the Penal Code.

The judge was not very concerned about being faulted for displaying a position before hearing the pleadings and deliberation, and he had no qualms about denying a principle enshrined in Article 13 of the Constitution. Nor did he care about the lawyers’ insistence that they had been unable to view the case file. Likewise, he had no reservations about the police reports, enclosed in the case file, that violated the defendants’ privacy and confirmed that they had been subjected to illegal police surveillance that breached the sanctity of the home enshrined in Article 9 of the Constitution. The lawyers’ words were all included in the transcript without much concern for their significance or impact. In this regard, Ben Salah’s interrogation became – contrary to the intent of the trial – an opportunity for his view on the policies he had planned to be heard.

Ben Salah’s Testimony: Adamancy About Cooperativism’s Success and Acknowledgement of Excesses

Ben Salah’s interrogation session was attended by 52 witnesses, all of whom the court insisted on hearing. They were farmers and merchants who had refused to join the cooperatives and were then thrown into prison on governors’ or delegates’ orders until they caved. They spoke about the losses they suffered and the humiliation they experienced. Ben Salah did not dispute their statements but said that he was shocked by what he heard and denied that he knew about the excesses committed by his assistants. The man seemed embarrassed by the reality presented to him. Nevertheless, he spoke about cooperativism with the same conviction that he usually did, insisting that he still believed that agriculture could only flourish via communes and cooperatives. However, he saw their hasty universalization as a mistake because it was done without regard for the lack of the technical human capacities needed to make it a success. When the court president asked him about the right to property and the Constitution’s protection of it, he responded that “the constitutional text protected the right but did not address the means of its disposition, and he believes that property should only be respected on a collective scale”, according to the ruling’s text. When the prosecutor asked him about his position on the coexistence of the public sector, private sector, and cooperative sector, he said that “this coexistence must be achieved in all economic activity, not in a specific sector”.

Ben Salah denied the charge of deception, saying, “I was one of the president’s arms. I receive instructions and implement them as I interpret them. I did not deceive the president, nor did he err. But I miscalculated, and I admit that I am responsible for the mistakes on my part. However, those mistakes do not warrant [trial by] the Supreme Court”. Later, in an attempt to curry favor, Ben Salah’s lawyer Hadi Ghalousi thanked the court bench, “stating that the atmosphere of the trial made him feel like he was facing not the Supreme Court but a party committee composed of party personnel devoted to their country and president and examining the case of a brother to them”. The court included his statement in the ruling document without comment, evidentially not seeing the ostensible partisanship it highlighted as a flaw undermining its justice.[7] But neither Ben Salah’s quiet speech nor his lawyer’s flattery was enough to refute a charge that the court had been created to prove.

The Deception is Proven and the President Must be Avenged

The allegedly misled president was not interviewed at any stage of the case’s investigation. Rather, the court was content to use his speeches as definite evidence that his intentions were good and his vision was correct. According to the court, the president rejected the idea of class struggle and insisted on national unity,[8] rejected oppression and believed that the cooperative policy was open to reform,[9] demanded concerted efforts from the entire nation to achieve social justice,[10] was open to criticism and reform, and saw no harm in retreating from cooperativism if it proved unsuccessful,[11] which showed that he had no knowledge of the breaches that emerged. Using the same approach, the court paid no attention to Ben Salah’s responses to the accusations. To prove them, it merely relied on excerpts from his speeches and an analysis of his positions, whereby it deduced that he is a person who provokes chaos wherever he goes and is inclined toward abuse and authoritarianism. Moreover, he was planning to violently take control of the party and country, exploiting the president’s absence for medical treatment, but was exposed thanks to the insight and resolve of the person against whom he conspired. Hence, on 24 May 1970, the court sentenced Ben Salah to ten years of imprisonment with hard labor,[12] in addition to convicting those charged as his accomplices.[13]

The first Supreme Court trial appeared to be a judicial remedy to a political and economic crisis that Tunisia’s autocracy had caused in the 1960s. Its works perfectly exemplify the concept of a judiciary that serves the regime, goes along with its plans, and takes pride in its allegiance to a leader and harshness toward anyone who displeases him. However, these works also constitute an important historical document that, via the testimonies, reports, and statements collected therein, paints a picture that today facilitates an objective analysis of the cooperative experiment far removed from the vilifying discourse that long prevailed and the glorifying discourse now prevailing among those who engineered it. Both these discourses neglect certain facts that remained locked in a case file intended as a means of political cleansing.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Ben Salah occupied the position of state secretary for planning, finance, agriculture, commerce, and industry. As such, he was Bourguiba’s most powerful and influential minister throughout the 1960s.

[2] Article 68 of the 1959 Constitution stipulates that, “The Supreme Court shall form when a member of government commits high treason, and the law shall govern its powers, composition, and procedures”.

[3] Parliament debates on 31 March 1970.

[4] Debates of the National Constituent Assembly, 1 June 2009 edition, p. 168. In his intervention, Ben Salah stated,

“I don’t know how this article came to be, and I don’t recall that we debated this subject. It would be odd for us to put in the Constitution that the president of the republic and members of government are responsible for high treason they commit and put to trial. At the point where [one of them is] tried, he would no longer be president of the republic or a minister. Naturally, if they [sic] become aware of the treason or the crime’s perpetration, [the person concerned] will be removed from the ministry or the position of president of the republic and become just like anyone else. Hence, this article is unnecessary, and I propose deleting it.”

[5] The Supreme Court Law stipulated that the court consist of a public prosecutor, investigating judge, and a president who is a senior judge, all of whom are appointed by presidential order, and four members whom Parliament elects from among its members. It also stipulated that the court take up cases “pursuant to permission issued by the president of the republic after consulting Parliament”.

[6] The people tried as Ben Salah’s accomplices were Amor Chachia, Tahir Qasim, Hédi Baccouche, Ibrahim Haydar, al-Munji bin Ahmad al-Fiqi, al-Bashir Naji, Hassen Babbou, al-Hadi bin Mansur bin Ayyad.

[7] In that era, judges belonged to the ruling party. They were not prohibited from membership until 1974.

[8] Four speeches that Bourguiba delivered on 27 December 1956, 17 February 1965, 31 March 1966, and 31 July 1966, in which he discussed national unity. From these speeches, the investigating judge concluded that Bourguiba rejects the disintegration of this unity via class warfare as he permits no part of the nation to believe, on the basis that it is the majority, that the others are no more than contemptible bourgeoisie.

[9] Two speeches Bourguiba delivered on 31 July 1966 and 1 March 1966, in which he affirmed that a person, as a Tunisian citizen, should be safe from oppression and subjugation and that the cooperative program was therefore open to evaluation and reform.

[10] Two speeches on 26 April 1965 and 1 April 1965: “Social justice is our goal, and the efforts of all components of the nation must be combined to achieve it”.

[11] In a speech on 19 April 1964, Bourguiba told citizens that if they perceived that the government had strayed from the set goal, they should not hesitate to say so openly as it was fully prepared to reform. In a speech on 27 October 1967, he said that he would not hesitate to abolish the cooperatives if they proved ineffective.

[12] During the night of 4-5 February 1973, Ben Salah managed, with the help of a guard, to escape prison. He traveled to Algeria and then France.

[13] Amor Chachia was sentenced to the same term (ten years). The other defendants were given five-year suspended prison sentences. Bourguiba appointed Chachia as general director of prisons once he completed his sentence, and he appointed Hédi Baccouche in a ministerial position. This shows his unique perception of his disputes with members of his party.