Amending Criminal Procedure in Egypt: Toward a Defenseless Defense

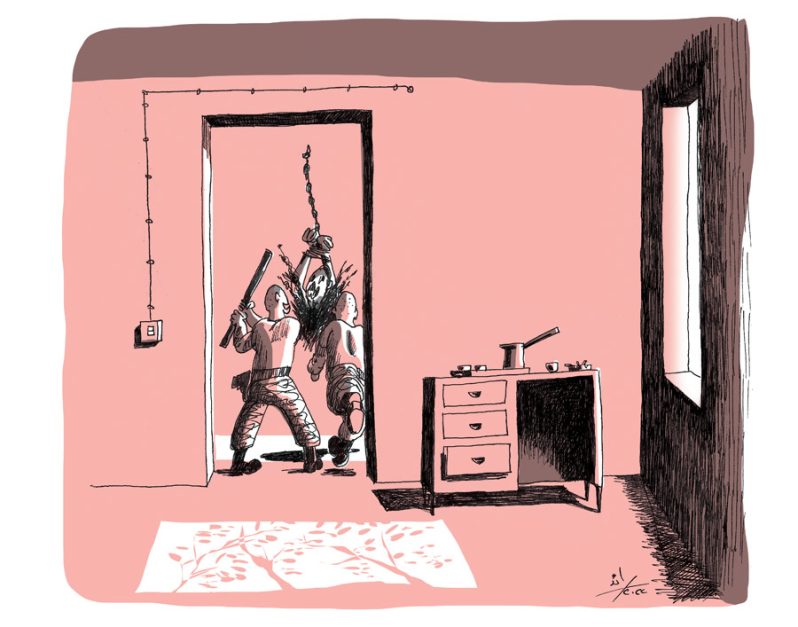

The right of defense is a cornerstone of a just and fair trial. It encompasses a number of guarantees ensuring its effectiveness, such as the right to know the charge, the right to view the necessary information and files, the right of the accused to defend themselves or appoint a lawyer, and the right to question witnesses. Recently, the Egyptian justice system has witnessed a serious disruption regarding the right of defense. Accused persons have been questioned without their lawyers, and lawyers have been attacked to prevent them from entering police stations to meet with accused persons.[1] Some public prosecution offices and courts have disrespected lawyers, and lawyers have been targeted for pleading in political cases, prompting some to refuse to attend or plead before certain courts.[2] Hence, it is clear that the Code of Criminal Procedure is being violated, and there is a need to strengthen the right of defense in this law and ensure that lawyers are protected while performing their job.

The proposed amendment to the Code of Criminal Procedure that Parliament is currently discussing addresses a number of articles that directly affect the right of defense. These amendments strengthen this right in the pretrial stage. Article 36 and 40 allow the accused to call their lawyer immediately upon arrest and require that they be notified of the reasons for the arrest, and Article 106 prohibits the Public Prosecution from questioning the accused or confronting them with other accused persons or witnesses without their lawyer present. Additionally, the proposal enshrines the accused’s right to a lawyer in court.[3] Article 237 also requires that the Bar Association prepare a roster of public defenders, notify the Public Prosecution and courts of it, and facilitate contacting the one whose turn it is. These articles reflect the proposal’s orientation toward seriously enshrining the right to a lawyer. This is a positive development as the right to a lawyer is one of the basic rights in a fair trial, with some considering it a gateway for enforcing other rights.[4] On the other hand, other articles reduce lawyers’ powers and give broader discretion to prosecutors and judges. The proposal also amends articles pertaining to in praesentia rulings and hearing witnesses, and it creates a system of remote trial. Consequently, there is concern that the proposal enshrines a formal right of defense with no actual effectiveness, for the right to defense does not stop at the physical presence of a lawyer before and during the trial; rather, it also requires that lawyers have powers that enable them to perform their role effectively.[5]

Stripping Lawyers of Their Powers During the Investigation Stage

The presence of a lawyer and their performance of their role during the pre-trial stage, i.e. the investigation stage, is essential and a guarantee of the right of defense.[6] However, the proposal strips lawyers of essential rights and tools during this stage, preventing them from performing their role effectively. Article 74 prohibits a lawyer from speaking without the prosecutor’s permission other than to present pleas and requests. A prosecutor’s refusal to give permission is noted in the record but there are no consequences.[7] Similarly, Article 94 allows the Public Prosecution to refuse to allow the defense to pose a question to a witness if “it is not related to the case or its phrasing is prejudicial to others”. This imprecise criterion allows the prosecutor to refuse any question on the pretext that it is not related to the case.[8] Hence, the proposal deprives the right of defense of its substance during the investigation stage and makes the lawyers’ performance of their role contingent on permission from the Public Prosecution. Instead, the roles of the two should be equal, especially as the Public Prosecution performs the roles of both investigation and indictment. Additionally, Article 107 allows the prosecutor to refuse to let the lawyer view the investigation before the interrogation or confrontation in circumstances wherein they decide to conduct the investigation in absentia.[9] This prevents the lawyer from obtaining a clear, complete picture and thereby obstructs them from properly performing their role.

The Trial Stage

a) Deeming All Rulings In Praesentia: How Does It Undermine the Right of Defense?

In a previous article, we mentioned that the proposal deems all rulings issued in misdemeanor matters to be in praesentia even if the accused is absent from the trial. This undermines the right to a trial in praesentia and the right of appeal. It also undermines the right of defense, as we shall explain.

The current law requires that in order for a ruling to be considered in praesentia, the absent litigant must have no justification for their absence.[10] However, the amendment abolishes this condition and deems rulings pertaining to anyone absent for some or all of the trial hearings to be in praesentia without regard for the reason for the absence.[11] Article 241 also stipulates that under circumstances wherein the ruling is deemed in praesentia, the court must conduct the investigation into the case as though the litigant were present.[12] This raises questions about the right of defense and presumption of innocence. By deeming the ruling in praesentia, the court would prevent the accused from defending themselves in person or via a lawyer, confronting the witnesses, refuting the evidence, or using other means of defense. As we mentioned in a previous article, it would also prevent the accused from filing an objection to the ruling [which would prompt a reexamination of the case by the same court] and hence leave them with just the path of appeal to defend themselves. The article also undermines the presumption of innocence stipulated in Article 96 of the Constitution, which links this presumption to fair trial guarantees and the right of defense in particular. The Supreme Constitutional Court has underscored this link, stating that

The presumption of the accused’s innocence of the charge is always coupled, from a constitutional standpoint and to ensure its effectiveness, with mandatory procedural means that are likewise considered, from another standpoint, to be closely linked to the right of defense. These means consist of confronting the evidence that the Public Prosecution presented to prove the crime and the right to refute said evidence with the exculpatory evidence that the accused presents.[13]

Additionally, this amendment portends a trend toward punishing the accused for their absence, irrespective of whether they have an excuse, by depriving them of their right to defense and subsequently convicting them, for an acquittal is inconceivable when no defense has been presented. The constitutionality of such an action is doubtful according to the Constitutional Court, which stressed in a previous ruling that “After the accused is properly notified, an excuse may arise preventing him from attending. Depriving him of the defenses with which he refutes the charge is not in accordance with the Constitution”.[14]

b) The Court’s Right to Refuse to Hear Witnesses: Stripping Lawyers of One of Their Basic Tools

The proposal also introduces amendments pertaining to hearing witnesses. Originally, Article 289 of the Penal Code allowed the court to recite the statements that a witness made in the preliminary investigation or evidence report if the witness could not be heard. In 2017, the article was amended to oblige the court to do so.[15] However, the current amendment reverts the article to its original form by giving the court the choice of whether to do so. It also adds a new paragraph allowing the court to refuse to hear a prosecution witness, even when the accused’s lawyer insists on hearing them, if it sees no need to do so, although the court must explain its refusal in its ruling. Lack of necessity is not a sufficient reason to prevent a lawyer from questioning prosecution witnesses before the court and debating them to refute their testimony and disprove the charge. Obstructing the lawyer in this manner clearly undermines the rights of the defense.

Additionally, while the first paragraph of Article 413 currently requires that witnesses who should have been heard at the first-instance level be heard by the Court of Appeal or by a judge whom it appoints for this purpose, the proposed amendment gives the court the discretion to decide whether to hear them. It stipulates that the court shall hear such witnesses “when it sees a need to do so to decide the case”.[16] Hence, if the Court of First Instance refuses to hear a prosecution witness or any other witness, the Court of Appeal can also refuse to hear that witness based solely on its assessment of the need to do so to decide the case and without any consideration for the right of defense.

The proposed amendments also complement the approach that the legislators took in 2017. Back then, Article 277 was amended to allow the court to decide which defense witnesses to hear but also to explain in its ruling the reason should it refuse to do so.[17] Hence, these amendments expand the court’s discretion with regard to hearing witnesses without any consideration for the defense’s right to call specific witnesses, whom the court may refuse to hear, or to question prosecution witnesses or any other witnesses whose testimony the court refuses to hear. There is therefore a clear trend toward depriving lawyers of one of their basic tools used to defend their clients in misdemeanor and felony matters. In a previous ruling, the Constitutional Court deemed that this deprives the defense of its effectiveness. The court stated,

It is inconceivable that the defense would be effective if there is no reasonable timeframe for preparation, if the accused is not informed of the witnesses that the indicting authority has prepared to prove its case so that they can be confronted and challenged, or if he is deprived of the mandatory means whereby he ensures that witnesses whom he freely selects appear in his favor…[18]

Remote Trial and the Right of Defense

As we mentioned in a previous article, the proposed amendment introduces a system of conducting investigations and trials remotely that openly undermines the public nature of the trials. The system also allows all trial and investigation procedures to occur remotely on the basis of no real criteria. Hence, there is a threat that all trials in Egypt will become remote trials.[19] The accused may only object to conducting the trial remotely during the first hearing. Moreover, the same court that decided to take this measure decides on the objection, which raises questions about the right to challenge and the court’s neutrality.

The extent to which the right of defense is guaranteed in remote trials is questionable. In this regard, the key measure may not lie in the execution of the trial remotely per se, but in how such a trial is conducted or its justification. As we explained, the text establishes no real criteria for resorting to this type of investigation and trial. Is it a matter of protecting the witnesses or victims? Or is it that some of the accused, witnesses, or experts are somewhere else and cannot be transported to the courtroom? The only real criterion for resorting to this measure is that the investigating authority or court sees fit to do so. The proposal does not even stipulate that this decision be explained. Consequently, it is a purely discretionary power of the judicial authority that is not even challengeable before a higher court. The Public Prosecution, investigating judge, or court may make this decision in order to expedite the case, for example, without any consideration for the right of defense, which requires that the lawyer take time viewing the documents and preparing the defense, pose questions to the witnesses, experts, and other accused persons, and interact with the judge and the investigating or indicting authority.

Additionally, what will the situation in remote trials be given that, as we explained, the proposal already undermines the right of defense in regular trials? If the accused and their lawyer, the court bench, and the witnesses are all in different places, how can the lawyer perform their role defending their client when they have been deprived of their basic tools?

Conclusion

In a ruling in 1994, the Supreme Constitutional Court held that

The guarantee of defense is no longer a luxury that can be forgone, and adhering to its formalities without delving into its objective truths is a regression from its true substance and clashes with the meaning of justice and its demands. Denying the guarantee of defense or restricting it in a manner that separates it from its intended purposes is merely a subversion of justice itself that prevents it from standing properly on its feet. [20]

Today, more than 20 years later, the proposed amendment to criminal procedure strips the right of defense of its tools and effectiveness as though the presence of a lawyer is merely a tool to complete the image of a fair trial. The proposal deprives lawyers of their basic tools for defending their clients and draws a sword called “disturbing or breaching order” over their necks in case they try to step out of line. In this regard, Article 245 of the proposal initially allowed the president of the hearing to write a report against any lawyer who does anything that could be considered a “disturbance breaching order” and refer it to the Public Prosecution. This would open the door for lawyers to be attacked while they work, as has already happened to some lawyers referred to investigation for what the court’s president deemed a breach of order.[21] After the Bar Association intervened, this article was amended in coordination with Parliament’s Legislative Committee. Now, if a lawyer breaches the order of the hearing or does something warranting criminal accountability, the court may write a “memorandum” for the lawyer (not a report) and refer it to the Public Prosecution, which must give the Bar Association advanced notice of any measure it takes against the lawyer. If the lawyer does something warranting disciplinary action, the memorandum is referred to the president of the competent court. Although the Bar Association’s amendment moderated the article, the threat of referral to the Public Prosecution or disciplinary action during and because of lawyers’ work still looms over them.

If the aforementioned articles are adopted as they appear in the proposal, the right of defense before the criminal courts will become no more than a formal guarantee of trial with no real effectiveness. We will be on the cusp of a new phase of trials in Egypt in which the courts and public prosecution offices have infinite powers while the defense is stripped of all its powers, which jeopardizes the fairness of trials.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

Keywords: Egypt, Fair Trial, Supreme Constitutional Court, Right of Defense, Criminal Law

[1] See Menna Omar, “Who Protects Egyptian Lawyers?” (part I, part II), The Legal Agenda, originally published in Arabic on July 3, 2016.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See, for example, Article 237 of the proposal.

[4] Debbie Sayers, “Protecting Fair Trial Rights in Criminal Cases in the European Union: Where Does the Roadmap Take Us?”, Human Rights Law Review, 2014, 14, p. 733-760.

[5] Ibid.

[6] See Supreme Constitutional Court, challenge no. 64 of judicial year 17, February 7, 1998.

[7] Article 74 of the proposal states, “Litigants and their attorneys may present to the prosecutor the pleas and requests that they see fit to present. Otherwise, the litigant’s attorney may not speak without the prosecutor’s permission. A refusal to grant permission must be noted in the record”.

[8] Paragraph 2 of Article 94 of the proposal states, “The prosecutor may always refuse to pose to the witness any question that is not related to the case or whose phrasing is prejudicial to others”.

[9] Article 107 of the proposal states, “The lawyer must be enabled to view the investigation at least one day before the questioning or confrontation unless the prosecutor deems otherwise in circumstances wherein he decides to conduct the investigation in the absence of the litigants”.

[10] See, for example, Articles 238, 239, and 240 of the current Code of Criminal Procedure.

[11] See Articles 238, 239, and 240 of the proposal.

[12] Article 241 of the proposal states, “In the circumstances stipulated in Articles 238, 239, and 240 wherein the ruling is considered in praesentia, the court must investigate the case before it as though the litigant were present”.

[13] Supreme Constitutional Court, challenge no. 13 of judicial year 12, February 2, 1992.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Per the 2017 amendment, Article 289 states, “The court must decide to recite the testimony presented in the preliminary investigation, in the evidence report, or before the expert if the witness cannot be heard for any reason”.

Article 289 of the proposal also states, “The court may decide to recite the testimony presented in the preliminary investigation, in the evidence report, or before the expert if the witness cannot be heard for any reason. If the defense insists on hearing the statements of a prosecution witness and the court sees no need to do so, it must include the reason for the refusal in its ruling”.

[16] Paragraph 1 of Article 413 currently states, “The Court of Appeal shall, by itself or via a judge it appoints for this purpose, hear witnesses that should have been heard before the Court of First Instance, and it shall satisfy any other shortcoming in the investigation procedures”.

The proposal states, “The Court of Appeal shall, by itself or via a judge it appoints for this purpose, hear witnesses that should have been heard before the first instance court whenever it sees a need to do so to decide the case, and it may satisfy any other shortcoming in the investigation procedures”.

[17] Per the 2017 amendment, “Litigants shall specify the names, data, and grounds for summoning the witnesses, and the court shall decide whose testimony needs to be heard. If the court decides that the testimony of any one of them need not be heard, it shall explain why in its ruling”.

[18] Supreme Constitutional Court, challenge no. 64 of judicial year 17, February 7, 1998.

[19] Article 570 of the proposal states, “The investigating body or the competent court* may take all or some of the remote investigation or trial procedures with the accused, witnesses, victim, experts, or claimant of civil rights and the party responsible for them that are stipulated in this law when it sees fit to do so”.

[20] Supreme Constitutional Court, challenge no. 23 of judicial year 14, February 12, 1994.

[21] See Menna Omar, “Who Protects Egyptian Lawyers?”, op. cit.