Appropriating Land for Green Capitalism in Southern Tunisia

Energy transition lies at the forefront of the government discourse in Tunisia, in line with the global push toward investing in alternative energy and thereby reducing fossil fuel use. This discourse constantly argues that this course – primarily the turn towards photovoltaic energy – will enable the country to overcome its energy deficit and stimulate investment (especially foreign investment), thereby addressing the economic crisis and increasing employment. However, these flashy headlines conceal the role these investments play in deepening the gap between regions and consolidating the same mechanisms of exploitation that exist in the extractive model. These mechanisms have brought nothing but misery to the inhabitants of the interior regions while reaping excessive profits for the investors without any real developmental or ecological benefits for the country.

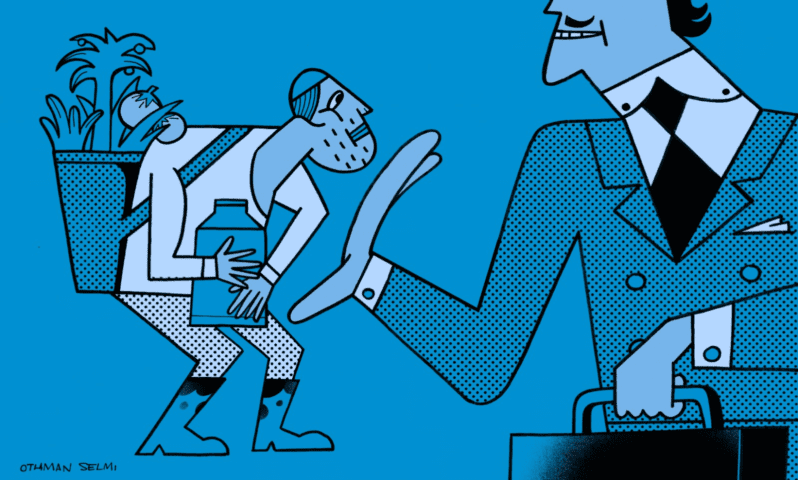

One unjust aspect of these investments concerns land exploitation. The construction of these projects, which primarily consist of solar or wind power plants, requires that the appropriate land be made available. Hence, President Kais Saied used his power to issue decrees to lift the obstacles preventing these projects from exploiting state and agricultural lands. As for collective and private lands, especially in the south, where real estate issues constitute an ongoing dispute between the authority and the inhabitants, the authority has gone into full swing using coercive methods to extend investors’ reach to these lands, as is currently occurring in the villages of Segdoud, Chenini, and Douiret. These villages might not mean anything to many people, but to the state and to some brokers, they constitute a natural resource to be served on a silver platter to foreign companies specialized in so-called “green energy”. Driving development and creating wealth by converting wind and sunlight into electricity through the exploitation of vast, “vacant” lands is being used as a pretext to appropriate these lands for the benefit of investors and so-called “green capitalism”.

Opening Legislative Locks for Capital to Exploit Protected Lands

To comprehend the challenges of exploiting lands for green capitalism investments and what the state is doing in this regard, we must first briefly review land categories in Tunisia. Lands are divided, based on ownership, in the following manner:

● Lands owned by the state. These consist primarily of the lands that were appropriated by the state after the end of colonialism (i.e. lands owned by the bey before 1956 and lands settled by French colonists). To these can be added the lands owned by local authorities and public institutions, as well as forests, mountains, roads, and so on. State property is divided into public property, which is subject to stringent rules of protection, and private state property, which enjoys less protection. It is also divided, based on its nature, into agricultural lands (which are subject to a special protective legislation, i.e. to double protection) and non-agricultural properties.

● Collective lands. These are lands that belonged to tribes, especially in the central and southern regions. Under the 1964 law, this type of land is overseen by management councils in consultation with the regional authorities. The law was amended in 2016 in a manner intended to eventually lead to the total liquidation of these lands. Hence, their status remains a matter of debate. The Communitarian Companies Decree opened the door for this type of land to be exploited (whereas it made no mention of state lands).

● Private lands owned by natural or legal persons.

Because each category is subject to its own legislation, the legal framework governing land is ramified. Consequently, the Ministry of Energy and Mines prepared a special guide for renewable energy investors to facilitate their access to the legal texts. The guide also mentions the steps foreign investors must take to enjoy these lands, which requires first and foremost the approval of the regional authority, represented by the governor.

However, the state – as part of its effort to encourage foreign investment in alternative energy – was not content to just exercise interpretation and ease procedures. Rather, it introduced successive amendments to the legislative texts, the gravest of which occurred via direct presidential decrees, in order to remove the need for agricultural lands to be reclassified before they could be exploited. Investors had been betting on exploiting private renewable energy of agricultural and state lands for years. This is demonstrated by the French-language document that the Ministry of Industry, Energy, and Mines published in March 2018 under the title “The Tunisian Solar Plan: An Action Plan for Accelerating Renewable Energy Projects in Tunisia”, as well as the proposal to form a committee bringing together the three ministries concerned (energy, agriculture, and state property) for the purpose of addressing the issues and suggesting solutions (or legal tricks, as appeared in the aforementioned document).

This was implemented in stages. The first stage focused on renewable energy projects for the purpose of self-consumption (with the excess energy being sold to STEG, the national gas and electricity company, and transported via its grid). The 2019 Investment Climate Improvement Law opened the door for these projects to be constructed on state lands through licensing. It also allowed them to be constructed on agricultural lands by totally exempting them from the condition that the agricultural classification of such lands be changed.

In the second stage, as land issues intensified, Decree no. 68 of 19 October 2022 on Enacting Special Provisions for Improving the Efficiency of the Completion of Public and Private Projects exempted all renewable energy projects (not just those aimed at self-consumption) from the condition that agricultural lands be reclassified “if the Technical Committee for Electricity Production from Renewable Sources establishes their feasibility”. This same decree also included an amendment to the Agricultural Reform Law allowing foreign capital to exploit agricultural lands just by forming companies in Tunisia and without requiring that Tunisians contribute to their capital or administration (several failed attempts to pass this “trick” in Parliament had occurred during the post-revolution years). Hence, while the discourse insists that state lands should be made available to the people who work them via communitarian companies, the presidential decrees go in the opposite direction, lifting legal restrictions that were established by agricultural decolonization and more or less withstood previous attempts to dismantle them and facilitate foreign and private investors’ access to agricultural and state lands, in addition to making it possible to exploit public forest, ocean, and water property with only the authorities’ approval.

Segdoud: Reviving Colonial Practices of Appropriating Tribal Lands

Before dismantling the legislative obstacles via the October 2022 decrees, the July 25 authority went into full swing approving concession agreements with foreign companies to operate photovoltaic power plants. These agreements were made in accordance with the 2015 Electricity Production from Renewable Sources Law. This law had passed with great difficulty because of opposition from the General Labour Union and other political and civil forces, which deemed it a gateway to privatizing the electricity sector. Opposition MPs even filed a challenge to its constitutionality, which resulted in an amendment requiring that energy contracts be examined by a parliamentary committee and approved by Parliament’s General Assembly, pursuant to Article 13 of the 2014 Constitution. However, the five concessions opened for tenders in 2018 were passed without any democratic debate via five presidential decrees on 14 and 19 December 2021. These decree-ratified concessions include the deal granted to French-Moroccan conglomerate Engie-Nareva in June 2021 to construct a photovoltaic power plant with a total capacity of 100 megawatts in the Segdoud region of Redeyef Delegation in Gafsa Governorate.

The absence of democratic debate is not the only issue with this concession. These investors were also granted approximately 400 hectares that the Ouled Sidi Abid tribe’s land management council considers to be part of its domain under the Collective Lands Law issued in 1964 and amended in 2016. The state, on the other hand, had previously deemed these lands to be part of its own property.

The Tunisian state thereby appropriated disputed lands whose status had not yet been settled, exploiting the haziness surrounding this category of land to allow foreign investors to exploit them. The text of the decree also exempts these investors from the controls imposed by the Protecting Agricultural Lands Law. All this occurred in the name of accelerating the completion of Tunisia’s solar plan and responding to the diktats of the global financial institutions, particularly the World Bank, contrary to the sovereigntist slogans employed by the government discourse in recent days.

The management council for the collective lands of Ouled Sidi Abid did not stand idly by in the face of the coercive practices targeting its lands. Needing more support and solidarity in this battle, it held a meeting with the Working Group for Energy Democracy in March 2022, which helped debunk the government’s marketing claims about employment prospects, the feasibility of direct foreign investments, and the returns they could bring to the inhabitants and to the region as a whole. The employment capacity of renewable energy projects is limited compared to other sectors as it is constrained to certain auxiliary services such as security, cleaning, and maintenance that must be performed by specialized companies that mostly do not exist in the region at present. This government marketing is part of the neoliberal discourse of the global financial institutions that seek to exploit the resources belonging to the peoples of the Global South for the benefit of the multinational companies of the Global North.

Segdoud constitutes a living example of green land-appropriation along the lines of French colonial practices designed to facilitate the colonists’ settlement of profitable fertile lands. The state is resurrecting these old practices today via officials latching on to neocolonialism. Until there is a real resolution to the status of this category of land that goes in favor of the inhabitants and contributes to local and regional development, the only way to resist these projects in the south (and center) is by supporting the collective land management councils opposing them.

Chenini: The Authority’s Local Apparatuses in Service of Foreign Capital

The Amazigh village of Chenini, located in the southern delegation of Tataouine, is also included in the agendas of foreign investors in so-called “green energy”. This area is home to strong winds that can be exploited to generate electricity. Because most of the lands are privately owned by the inhabitants, the Spanish investor planning to construct a project there has, with the help of the local and regional authorities, inclined toward unfair leasing contracts to access the lands.

Approval by the regional authority has turned into a means of pressuring the inhabitants to lease their lands even though many of them oppose it. Consequently, the offices of state representatives in the region now operate as marketing firms for foreign investments.

This manner of dealing with the inhabitants raises multiple questions about the nature and orientations of the ruling regime following 25 July 2021. The presidential discourse calls for engagement in the communitarian companies project and for full support for facilitating local and regional exploitation of resources by the inhabitants, whereas the same old practices of harnessing the country and people for foreign capital without any democratic oversight continue. The end result is that the authority becomes a pliable tool for achieving foreign capital’s desires as if it were the actual ruler.

Bourj Essalhi: The Living Memory of the “Dark Side of Renewable Energy”

The coupling of “energy transition” and “green investments” with authoritarian methods is not new. Rather, it is reminiscent of what occurred in the early 2000s in Bourj Essalhi. The El Haouaria wind power plant was not only the first renewable energy power plant to be established in Tunisia (not counting the hydro plants constructed in Segdoud) but also the first link in the chain of expropriating lands from the inhabitants for such projects.

The first phase of the project began in 2000 with the installation of 32 turbines in the Sidi Salem region (El Haouaria) with a capacity of approximately 11 megawatts. In the second phase, in 2003, the project was expanded to the Henchir Gharmene region. In the third phase, in 2009, it was expanded to the Bourj Essalhi region.

This third phase was marred by many transgressions that deprived the inhabitants of their rights over all lands in the region. This occurred, firstly, through the recategorization of a large portion of these lands from “agricultural lands” to “forest lands” so that the state could more easily dispose of them and the construction could begin. Secondly, the inhabitants’ remaining lands were made available to STEG via degrading lease contracts that residents were forced into through intimidation and threats emanating from Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s authoritarian regime on the pretext of a national project that would benefit the region and the country as a whole. A report by the Tunisian Forum for Social and Economic Rights (FTDES) – which is the source of the quote in the heading of this section – reviews these transgressions and the harassment that compelled landowners to sign off on leasing their lands at bargain prices. The wind turbines directly damaged the inhabitants’ revenue from farming and herding, not to mention the potential health repercussions of the proximity of the wind turbines to their houses.

The revolution freed the inhabitants of Bourj Essalhi from the power of fear. However, after Ben Ali’s departure, STEG responded to their protests against the project and their struggle to settle the status of this land exploitation and appeal the leases with punitive practices, such as deliberately not performing necessary maintenance on the power grid. This collective punishment caused repeated power cuts to the residents’ homes “until they [paid] their overdue bills”. The company even deprived new subscribers from the village of electricity until the other inhabitants paid up. However, their struggle in coordination with the Bourj Essalhi municipality (after its council was elected), FTDES, and the Tunisian Human Rights League resulted in a negotiation process that led to an agreement in March 2021.

The coercion, pressure, and intimidation that occurred before the revolution in Bourj Essalhi are being reapplied today on the inhabitants of other regions, albeit for the benefit of foreign investors, always in the name of generating electricity from renewable sources. The growing role of middlemen and brokers for the purchase or lease of lands in Gabes may be another example of this. Documents obtained by the Stop Pollution movement in Gabes reveal that approximately 5,000 hectares are set to be exploited for photovoltaic and wind power with the tacit agreement of the local and regional authorities.

So far, contrary to the president’s slogans, the state and its apparatuses are playing a negative – if not complicit – role by facilitating foreign capital’s access to the country’s resources and marketing a fallacious discourse about energy transition and countering the effects of climate change. It is helping to whitewash companies considered major global polluters and neglecting to hold the wealthy nations responsible for the profound effects of climate change on our countries. The state should be offering support to farmers to help them confront drought and extreme natural events such as floods by making wealthy countries pay their environmental debts to the countries of the Global South. Instead, it is following the recipes of global financial institutions that are controlled by wealthy countries and help them appropriate these farmers’ lands so that it can borrow from these institutions and thereby create new markets for big companies. The result is that the state is only increasing Tunisia’s debts and deepening its economic crisis.